A super idea?

Should we have let people raid their superannuation during COVID-19?

Thirty-two-year-old Cam Mighell is one of more than 3 million Australians who accessed their superannuation during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mighell took out the maximum amount of $20,000, leaving him with a remaining super balance of $6000.

His reason: “Because I was allowed to, and I thought it would be fun,” he said.

"I don't think I've made a financially sound decision ever, so it seemed pretty on par with the rest of my life choices.

“I was getting JobKeeper, plus I was also working in a school, which kind of wasn't allowed, so I was like the richest I've ever been during the pandemic.”

Retirement has never been on Mighell’s mind, “I’ve never thought about retirement,” he said.

“Making 70 is touch and go anyway.”

Critics argue that the scheme will cost individuals and taxpayers for decades to come, so why did the government grant people access to their super?

The policy

The Federal Government set its sights on superannuation within weeks of the first pandemic lockdown. Those deemed financially impacted were able to access two lump sums from their fund.

People could access up to $10,000 of their superannuation between 20 April and 30 June 2020, and a further $10,000 between 1 July and 31 December 2020. Those eligible were either unemployed, receiving welfare payments, or had their hours or sole trade income reduced by 20 per cent.

A statement put out by Treasury outlines the Morrison Government’s reasoning:

“While superannuation helps people save for retirement, the Government recognises that for those significantly financially affected by the Coronavirus, accessing some of their superannuation today may outweigh the benefits of maintaining those savings until retirement.”

The early release of superannuation was the Federal Government’s first stimulus package aimed at addressing the impacts of the coronavirus.

Was the government too quick to grant Australians access to their super funds?

The opposition party at the time certainly thought so.

“One of Labor’s most grave concerns is the threat posed to retirement incomes and the stability of the financial system by the expansion of the early release of superannuation,” Senator Kristina Keneally said.

“Drawing from superannuation should only be done as a measure of last resort.”

Who dipped into their super?

More than 3 million Australians were tempted by the golden carrot: a once off chance to raid their super fund, the pot of gold that you are only allowed to touch at 67 years of age, likely older for those only just starting working life.

For more than 1 million of those people, the deal was so tempting they withdrew twice.

This brought the total number of withdrawals to 4.55 million, totalling $37.8 billion of super requested for early release.

Young people raided the most

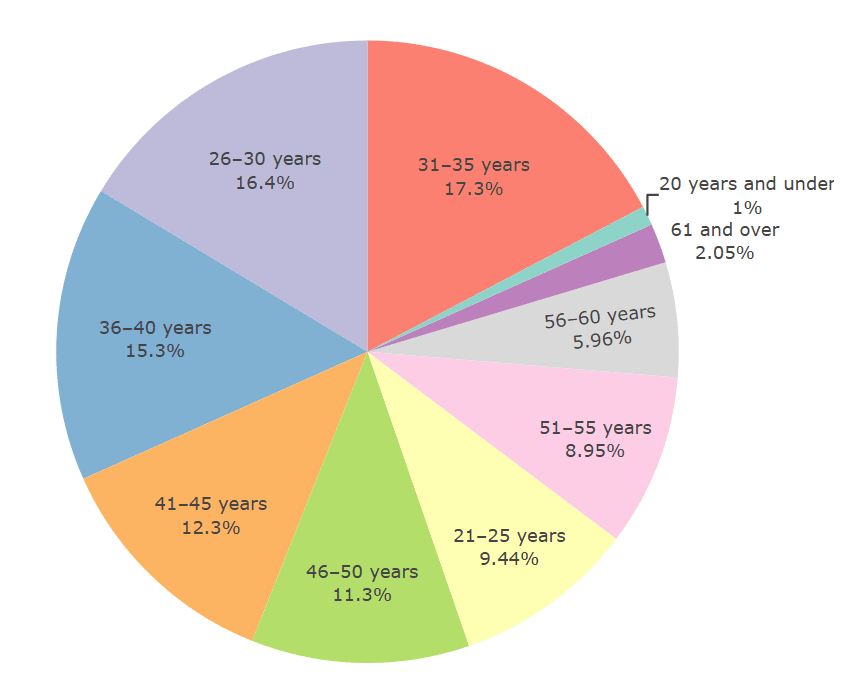

Here is a chart breaking down the number of approved superannuation withdrawal applications by age.

People aged between 26 and 40 accounted for 49 per cent of total applications made. Eighty-two per cent (594,000) of people that completely emptied their fund were from the 35-and-under age bracket.

Alistair Bush, 28, decided to withdraw $13,000 from his super, which equated to just under half of his fund balance, to buy a car.

Bush felt the money would be more beneficial to him during this time than at retirement, with his young age contributing to his decision.

“I’ve got time still,” he said. “I am fortunately quite young and I’m not really too worried.”

However, experts fear that younger Australians will disproportionately bear the consequences of the earl-release scheme.

An analysis by the Super Members Council predicted that a 30-year-old who withdrew $20,000 from super could be left with about $93,600 less at retirement.

Why such a large difference? Association of Superannuation Funds Australia Head of Policy and Advocacy James Koval said it is the combination of lost compound interest and withdrawing at the bottom of the market.

“It is not only the amount that you’re taking out that you are missing out on, but it is the compounding growth and compounding interest over time,” he said.

The impact on women

Prior to the early release scheme female workers were already on average retiring with 30 per cent less than their male counterparts. Women in Super Policy Advisor Ella Melican anticipates that the early release of superannuation will widen this gap even further.

On average Australian women are retiring at 54 years of age, with a median balance of $130,714.

“But what that data doesn’t show is the third of women who are retiring with no super at all,” Melican said.

“And now because of the COVID-19 early-release scheme an even greater number of women will reach retirement with no super or very, very minimal super.

“For coupled women, especially if they are part of that nearly one fifth of women who are experiencing coercive control, they retire relying entirely on either the Age Pension, or on their partner, both of which are very dangerous and insecure ways to live.”

Melican said the outcomes for single women retiring with zero super are even worse.

“They are living on the poverty line. Their costs are much higher, especially if they don't own a house at retirement age,” she said.

“We know that there is such a strong direct correlation between financial insecurity or instability and a lack of physical insecurity and safety.

“The way that our age pension is designed, it's really meant to be a safety net, it doesn't support people to retire with dignity, safety, and security.”

Melican said there is a continued expectation that women will access their super to pay for policy shortfalls.

“Unless we stop all of these little areas where super is being whittled away, we are continuing to condemn generations of women to retiring with lower balances and often into poverty,” she said.

Tasmanian Nell Imber had been experiencing chronic shoulder and neck pain for most of her adult life.

Working low-paying jobs while also raising two children made saving an extra money near impossible.

The early release of superannuation during the pandemic was her saving grace.

“I’d always wanted breast reduction surgery but never had the money,” she said.

Imber was already in the process of receiving medical sign off from a surgeon to allow her early access to her superannuation.

The early-release scheme just expedited the process.

“I just decided I’d had enough, and I couldn’t live with that chronic pain anymore,” Imber said.

She was one of 725,000 Australians that wiped their super balance completely during the scheme.

She used her balance of $18,000 to get a breast reduction and to pay for extra expenses.

“For me it was a no brainer,” she said.

“It was life-changing surgery.”

The short-term economic impact

We can’t know for certain the long-term impacts of the scheme, but experts have analysed the short-term impacts of the scheme.

The scheme provided a lifeline at short notice without impacting the current government’s budget. But on an individual level, how did this scheme impact those who opted to withdraw?

The Super Members Council found that most people thought about the decision to withdraw for less than a week with more than a quarter deciding to withdraw within a day of hearing of the scheme.

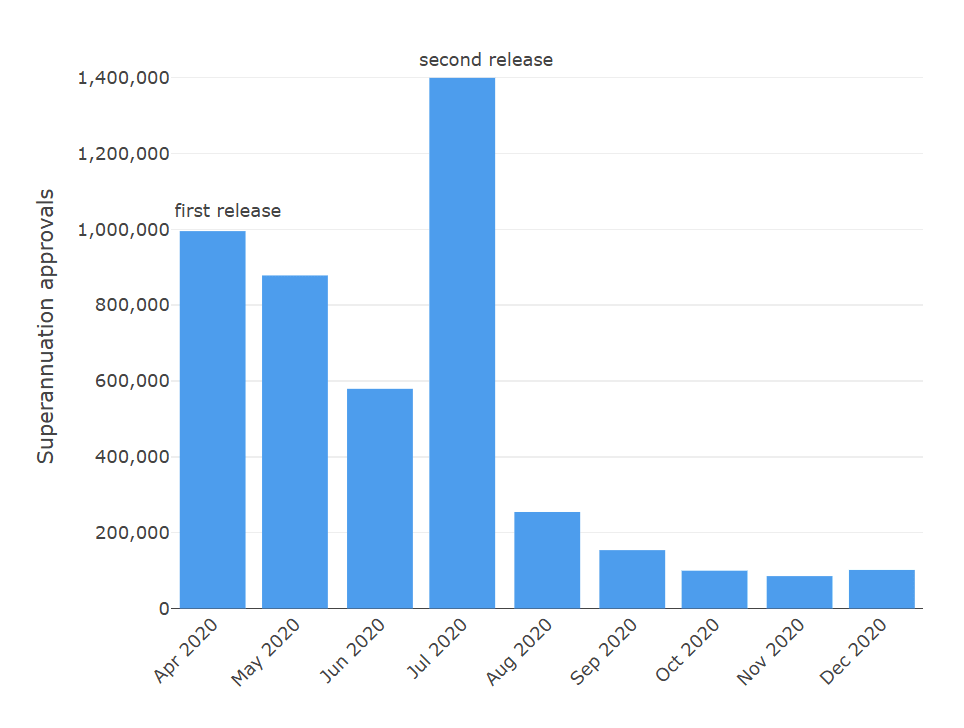

This chart shows the withdrawal applications for each month of the scheme.

The majority of applications were concentrated to the first month of each round, with nearly half being made in the first fortnight of the respective releases.

A report by E61 Institute found that people who withdrew from their superannuation did not feel more satisfied with their financial situation.

“You would expect that if it was really well targeted that when people withdrew the money, they should have been happier with their financial situation,” E61 Institute Research Manager Rose Khatter said.

“And actually, we found that there wasn't really any impact on people's satisfaction with their financial situation, which is surprising given its intended goal.”

Khatter said the scheme was not well targeted to those who were financially stressed.

“We probably should have had something that was a little better targeted to ensure that it was actually being utilised by the people who are most adversely affected by the economic shock,” she said.

“But what we found was people who accessed their super early tended to be higher income than those who were JobSeeker supplement recipients.”

Khatter said that people who accessed the early release scheme spent less than those who received other support measures.

“A lot of it ended up going into savings, which kind of defeats the purpose of having people access money to spend in the economy to try and stimulate it,” she said.

Crawford School of Public Policy Professor Robert Breunig said people that withdrew their superannuation also ended up being unemployed for about 10 weeks longer on average than people who did not take the money out.

“People got that money and then they weren't under so much pressure to go back to work,” Breunig said.

“They stayed out of work for longer using the money.”

Breunig found that those who withdrew would have ordinarily spent less time on benefits.

“They tended to have higher pre-COVID wages and superannuation balances, and were more likely to be married, male, and have children,” he said.

“There was also no evidence that those who stayed out of work longer because of withdrawing their super found higher-paying jobs.”

What is known of the longer term

The Super Members Council anticipate the cumulative cost of the scheme in forgone earnings tax and increased reliance on Age Pension payments to be around $70 billion by 2085.

Koval agreed, stating that people who accessed their superannuation would have less money when they got to retirement.

It is clear that the lost compound interest over time is significantly greater than the original amount withdrawn.

“It's important to be cautious about opening that door of early release too widely because of those long-term consequences,” Koval said.

Koval said the scheme disproportionately disadvantaged poorer Australians.

“Asking people to tap into their personal savings will always mean that those with less means and less money at their disposal will be worse off,” he said.

“Just due to the circumstances in which the policy was implemented, people may not have been aware of the future ramifications.

“But that is not the fault of those individuals who were accessing a lifeline during a very uncertain period.”

Lessons learned

“There can be some circumstances, certainly some extreme or last resort circumstances where accessing superannuation on compassionate grounds can be understood,” Koval said.

However, experts agree that women and people of lower socio-economic status will disproportionately feel the impacts of early release schemes.

Superannuation balances seemed to be back for the taking with the Coalition’s housing policy, proposed during the federal election campaign.

The policy proposed to allow first-home buyers to access their superannuation balance and put it toward a house deposit.

However, the Super Members Council warned this would do more harm than good, estimating that it could hike housing prices by more than 10 per cent and make home ownership further out of reach for young Australians.