Tool or temptation? AI use evolves in higher ed

The real question is about responsible use of AI, say educators and students.

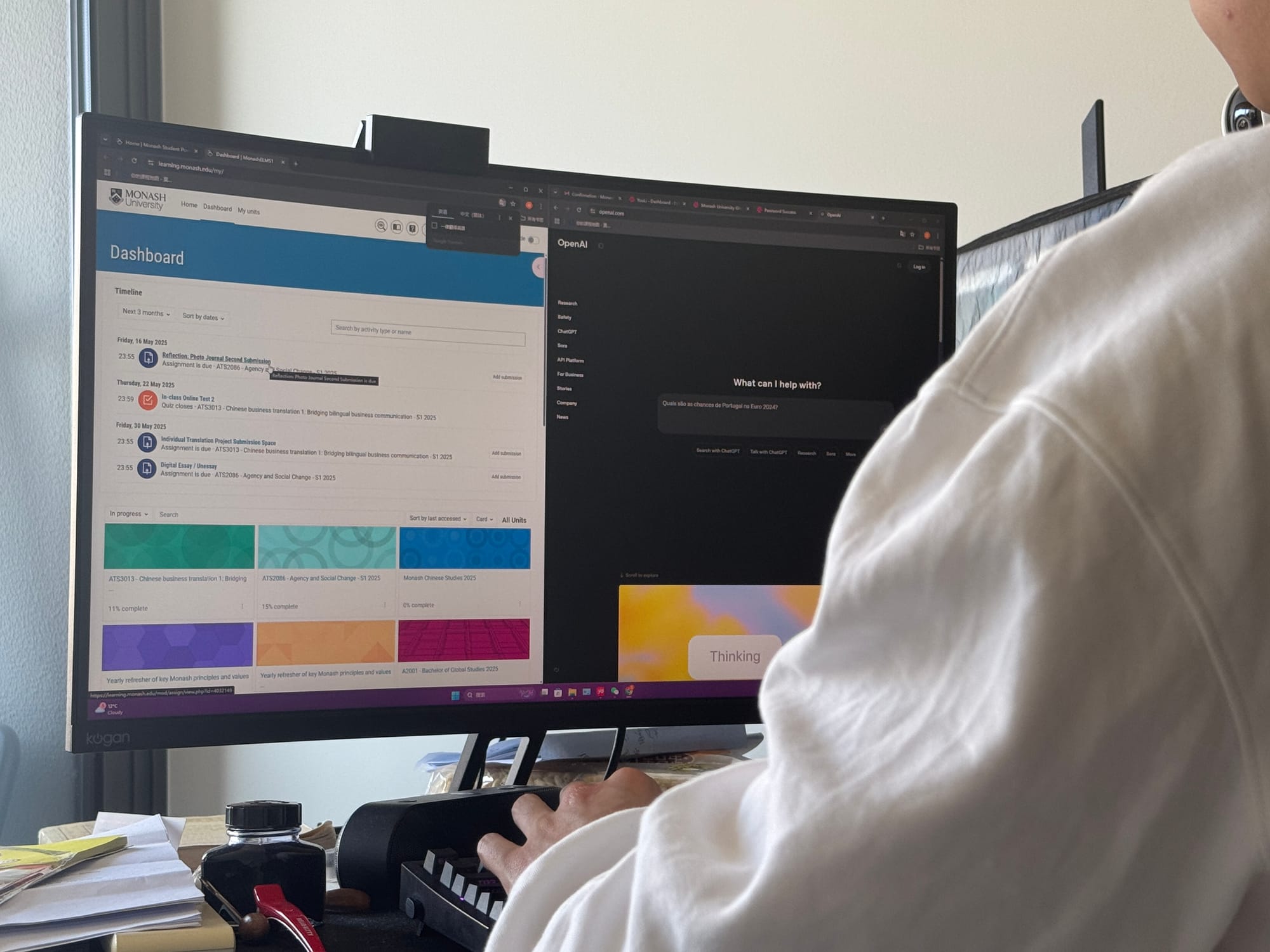

With Monash University recently updating its academic integrity policy on student use of artificial intelligence (AI) in assessments, we might ask: do students and teachers think of AI an educative tool — or a temptation?

The new policy, introduced last year, specifies particular conditions for the use of AI in assessments. A key condition is that students must declare their use of AI.

It is a move that allows for adaptation of rising AI use in higher education and consideration of the ethical challenges it brings.

Tool or temptation?

For many students, generative AI could be both a productivity booster and a potential shortcut.

In 2023, several universities initially banned AI tools like ChatGPT, amid fears of widespread plagiarism.

But as the technology became embedded in daily academic life, universities began shifting toward regulation instead of restriction.

Monash’s new approach treats AI a bit like how a calculator is used in a test — allowed under certain conditions and only when transparently declared.

Supporters say this aligns with modern workplaces, where AI is already a tool for enhancing productivity.

Critics worry, however, that it may lead students to avoid critical thinking and rely too heavily on automated content.

Monash University lecturer and filmmaker Dr Victor Araneda Jure believes AI literacy should be part of modern education.

“We shouldn’t outright ban AI — instead, we need to guide its use in education,” he says.

“If we don’t teach students how to use AI, they may develop over-dependence, making it harder for them to deeply learn and understand knowledge."

Jure says the creative process — particularly in film, writing and research — demands individual reflection and understanding that AI cannot replicate.

Academic voices

Monash educators and students are exploring how AI can be used ethically and effectively.

Master of Business student Jiating Zhang said ChatGPT was an effective tool for brainstorming.

“I use ChatGPT to help generate ideas, but I never copy its content directly,” Zhang said.

Zhang said while AI helped with structuring and grammar, the real work needed to be his own.

“You need to find a balance where AI assists but doesn’t replace your thinking.”

He described AI as particularly helpful during tight deadlines when time for reading and research is limited.

Zhang also emphasised the importance of fact-checking.

“Sometimes it provides convincing answers that sound right, but when I checked the original sources through the Monash Library, I found it was completely wrong”.

This led him to rely on AI mainly for guidance and not for content generation, especially when academic accuracy matters.

“AI can’t replace reading. It might simplify things, but without reading deeply, you miss the nuance,” Zhang said.

Master of Education student Baichuan Jia agrees on the vital importance of deep reading.

“ChatGPT helps me save time, especially when summarising articles,” Jia said.

“But I never let it write my assignments.”

Jia believes AI can manage basic tasks, but original thought and logic must come from the student.

“Creativity still needs to come from us,” Jia said, raising concerns about how AI affects learning habits.

“If people become too used to relying on AI, they might stop thinking for themselves.”

Jia said in the field of education, overuse of AI could undermine human interaction.

“In early childhood education, teacher-student communication is essential for emotional and cognitive development. AI can’t replace that.”

Jia sees AI as a tool best suited for assessments and background support, not for designing meaningful educational experiences.

Bachelor of International Relations student Guanlin Ge uses AI to support research and thinking.

“I use AI to help summarise social movements and discuss philosophical questions,” Ge said. “But I always fact-check everything.”

Ge said misinformation was a real concern and relying blindly on AI could lead to serious mistakes.

“If you don’t verify it, your judgment can be compromised."

Ge also shared an example of an AI-assisted discussion that challenged his thinking.

“I once asked ChatGPT whether a man who sacrifices his parents to bring resources to humanity is selfish or selfless,” he said. “The discussion helped me explore multiple perspectives.”

For Ge, AI can be a tool to expand one’s thinking, but only when students engage with the ideas critically.

All of the Monash people interviewed for this story agreed that AI is a support tool — not a substitute for effort.

When used critically, it could enhance learning. But without proper guidance, it could also diminish it.

Navigating integrity and the future

The shift in Monash’s academic integrity policy reflects the evolving nature of assessment in the AI era. Now, the question is not whether AI should be used, but how it should be used responsibly.

Under the updated guidelines, students must declare how they used AI in their assignments. This promotes transparency and encourages reflection.

Submitting AI-generated work without acknowledgment is considered misconduct.

Teachers are also adjusting. Some have added AI-specific criteria to rubrics — for instance, allowing grammar assistance but banning content generation.

Others are redesigning assessments to include presentations or case-based analysis that AI can’t easily mimic.

Zhang is reassured that responsible AI use is no longer taboo.

“It’s good to have clear rules. That way, we know how far we can go,” Zhang said.

Monash is part of a broader shift across Australian universities using AI for assessment.

Institutions such as the University of Sydney and RMIT have moved to embrace regulated AI use.

Last year, RMIT formally permitted AI use for certain tasks, positioning it as part of future job readiness.

Welcoming AI into classrooms means rethinking what learning looks like.

Just as calculators reshaped mathematics and Google redefined research, AI is transforming how students generate and evaluate knowledge.

Skills like crafting prompts, evaluating results and checking sources are becoming central to higher education.

Over the next few years, universities will likely continue adapting to AI’s influence.

This may include plagiarism detection tools, AI-specific training and restructured assignments.

The key question will shift from "Can students use AI?" to "How can we measure genuine learning in the age of AI”?

As Jure says, “We can’t stop technological progress".

“We need to guide students to use it appropriately so they can better understand knowledge. Learning and research are never superficial — they require deep reading, investigation and comprehension.”