Indigenous Language COVID-19 Warnings: "Protecting our mob in the bush"

A team of interpreters have worked tirelessly to spread the message about COVID-19 dangers to remote and vulnerable Indigenous communities.

BY JACLYN HOLLAND

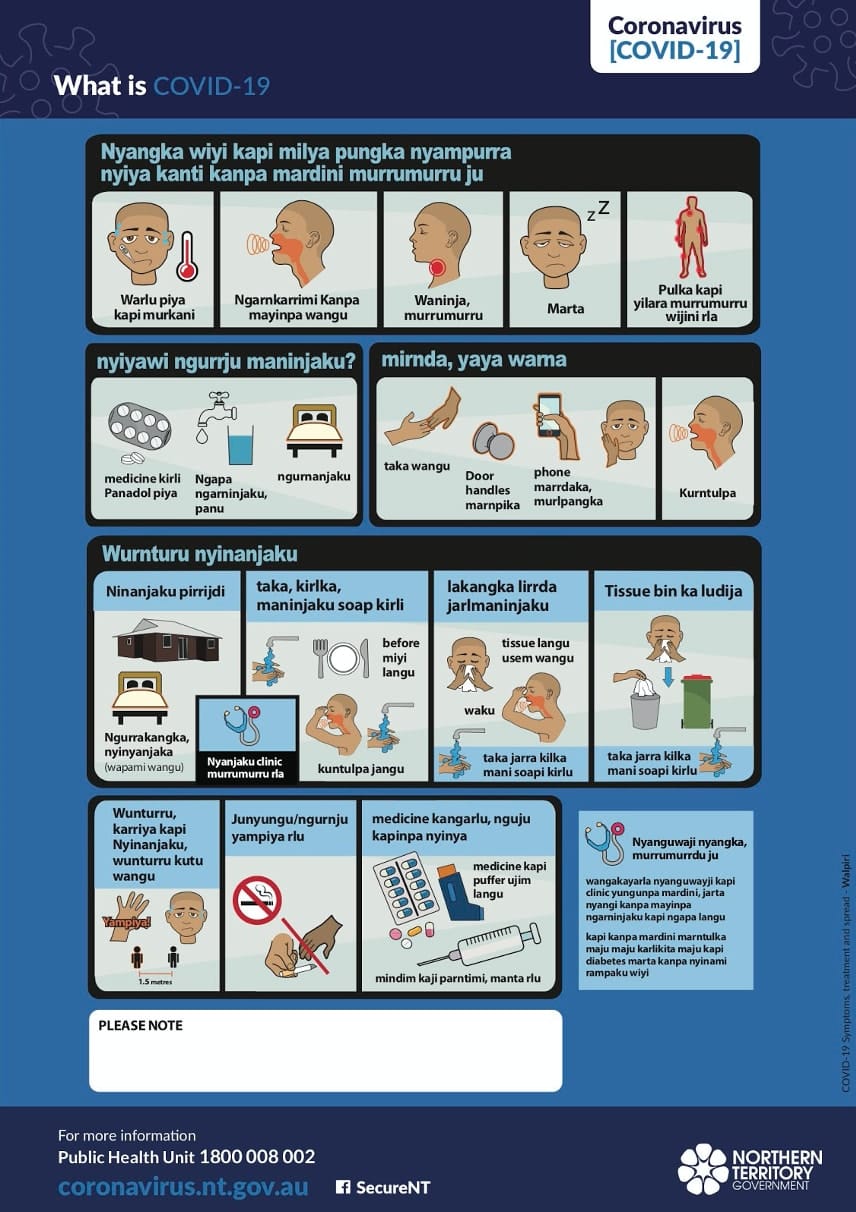

Translating COVID-19 health advice into Indigenous languages has quickly become a top priority in the Northern Territory to protect vulnerable Indigenous communities from the deadly virus.

While people aged over 70 have been strongly advised to stay at home and self-isolate, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people over the age of 50 have been given the same advice, with Indigenous Australians generally at a “greater risk from COVID-19”.

Posters and videos have primarily been used to help spread health advice in a variety of Indigenous languages spoken from Alice Springs all the way up to the Tiwi Islands.

Renowned Central Australian artist and advocate Chips Mackinolty has been working with Indigenous language for almost 40 years and said its many variations are part of the soundscape of the Territory.

“Living in the Territory, English is very much not people’s first language – especially amongst older people – it might not even be their second, third or fourth language,” Mr Mackinolty said.

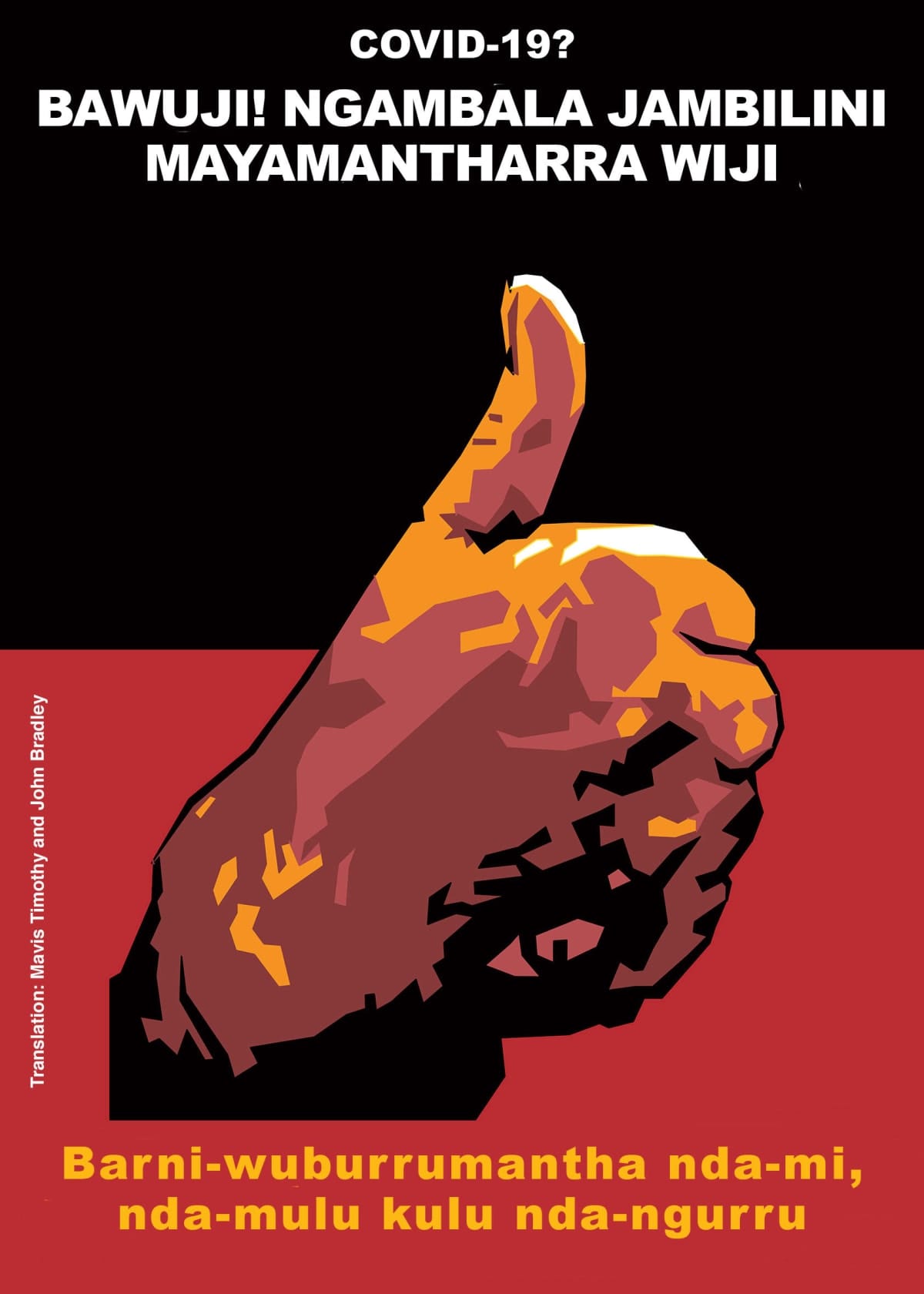

Mr Mackinolty designed a poster depicting one way to prevent the spread of COVID-19: greet friends and family with a thumbs up rather than hugging, or shaking hands.

A variety of Indigenous languages adorn the posters, each leading with the message that “we’re all in this together” and ending with a different piece of health advice.

For example, “washim yu bingga garra bigmob soup en woda” is Kriol for “wash your hands with lots of soap and water”.

The graphic has also been featured in a series of 18 videos – each in a different Indigenous language – created by the Northern Land Council and the Northern Territory Government’s Aboriginal Interpreter Service.

Mr Mackinolty is helping share the work completed in the Territory internationally, to further enable COVID-19 health advice to be communicated across multilingual communities around the globe.

“It’s been a huge effort [for] linguists obviously to get the messages right in different languages – there’s some concepts that are quite difficult to translate,” he said.

Rather than medical terminology, he explained some of the most challenging barriers to overcome in this situation are more culturally based.

“Being a communal society, it’s been very difficult to say ‘well you can’t sit down with a big bunch of people’,” he said.

Monash Indigenous Studies Centre professor John Bradley was one of the academics who translated health advice.

Having worked in the Borroloola area near the Gulf of Carpentaria for more than 40 years, Dr Bradley is one of the few people left in Australia who can fluently speak Yanyuwa.

Working alongside retired Indigenous health worker and Yanyuwa elder Mavis Timothy, he said their approach to the translations was to be as direct as possible.

“There’s certain things on these posters that from a Western perspective people might think ‘that’s disgusting’,” Dr Bradley explained in regard to one poster stating not to spit.

“But it’s taking the consideration that these things happen in communities, and let’s be upfront and honest about it.”

While many of the languages chosen for translation have been those with a significant number of speakers, the Yanyuwa language is now only spoken by a handful of people.

But to Dr Bradley this does not undermine the importance of the task.

“When I started doing the translations for the Yanyuwa [posters], one of the first responses was ‘we don’t need those – everyone speaks English’,” he said.

“Now that wasn’t even from an Indigenous person, that was from a white person.”

The translated posters have been posted around the town of Borroloola, about 10 hours drive south-east of Darwin, and have received some positive responses, Dr Bradley said.

“I’ve already heard from Mavis that she’s been there with her grandchildren and she’s been reading [the posters] to them.

“And they’ve gone back and have been reading them to their other friends, so they’re sort of assisting in people being aware of their own language.”

Health clinics across the Territory are also dedicated to translating COVID-19 health advice into Indigenous languages.

The Katherine West Health Board (KWHB) would regularly hold community meetings or visit individual homes across the eight communities it services to pass on information.

These yarns, as they were also called, would involve community elders translating the information to the local language.

KWHB CEO Sinon Cooney said once social gathering restrictions were put in place, much of its advice on COVID-19 had to go online.

“The staff that would normally travel quite freely and talk to people are now grounded in Katherine,” Mr Cooney said.

“So it’s very limited what we can do on the ground now, other than through our social media.”

While he said the Northern Territory Government has provided some useful resources on COVID-19 in a range of Indigenous languages, the KWHB often asks local Indigenous health workers if they could translate the information for people in their area.

“There’s a far higher uptake rate if it’s someone you recognise, someone you relate to,” he said.

With 10 different Indigenous languages spoken across the Katherine West region, this has been an enormous task that is not likely to end soon.

“We’ve been working around the clock to develop resources that are meaningful for our mob,” he said.

“We’re getting there, but there’s still a lot more to be done.”

While the Northern Territory has the lowest number of COVID-19 cases in Australia as of April 20, Mr Cooney said health clinics are still on high alert.

“This isn’t something that even once the restrictions are lifted that it just goes away – it looks to be a problem for us long into the future,” he said.

“Until there’s a vaccine, or there’s an adequate treatment, we’ll be pretty cautious about protecting our mob in the bush.”