AUKUS through a Southeast Asian lens: The pearls and pitfalls

Analysts are urging AUKUS partners to chart a course that ensures the new submarine deal won't send the Indo-Pacific into disorder.

Strategy analysts are urging AUKUS partners to take steps to reassure Southeast Asian nations that the new submarine deal is about preventing, not starting, a war.

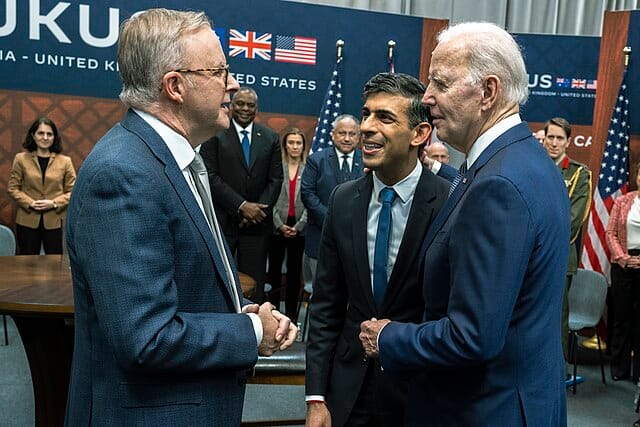

The deal, which has been the subject of global debate since its announcement in San Diego last month, is one of the first endeavours by the alliance of Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom to strengthen Australian border security and combat China’s rising aggression.

Yet analysts say the deal has the potential to tip ASEAN and the Indo-Pacific into disorder — or create an international reorder — depending on how the alliance charts its course.

The submarine program will take place in multiple phases over the next three decades, with a shared expenditure of up to $368 billion for eight nuclear-powered vessels, Nine newspapers reported last month.

While the staggering costs have raised eyebrows and prompted debate, the biggest concerns come from Southeast Asia, on whose straits the vessels will be operating.

Stuck in a tug-of-war between China and the West for hegemonic influence, regional players are fearful of AUKUS potentially inciting an arms race and compromising nuclear non-proliferation — which would drastically change the security landscape of the Indo-Pacific.

China has been the first to point fingers, and was reported in The America Times accusing the alliance of a "typical Cold War mentality" and having "disregarded the concerns of the international community" for personal geopolitical interests.

But states like Singapore, Vietnam and the Philippines have displayed cautious optimism since the trilateral partnership was announced, with hopes for contributions to peace and stability in the region.

Their counterparts, Malaysia and Indonesia, are far less idealistic.

The Malaysian Ministry of Foreign Affairs last month released a statement reiterating its stance for all parties to respect and comply with the Malaysian regime and international laws in relation to the use of nuclear-powered vessels in its waters. Earlier, Indonesia encouraged Australia and other parties to "advance dialogue in settling any differences peacefully".

University of Malaya research fellow Collins Chong Yew Keat, a foreign affairs and strategy analyst, says Malaysia is stuck in a tight spot between trade obligations with China and maintaining ASEAN neutrality.

“I've always argued for the need for Malaysia to come up from this to be free from this trap of Chinese influence. We all understand the complexities of the issue involved, that we are too reliant on interdependence, that the over-dependence on Beijing's economic mine has been too ingrained,” Collins says.

“And we’ve been trying to ensure that for the past many decades we've aligned to this non-affiliation neutrality approach, because we thought that will be the best option going forward by not aligning with any rivalling power or conflicting parties.”

But Collins insists the arms race has already begun, and has been ongoing for four years with China amplifying its defence measures in the South China Sea.

“It's really important for Malaysia to not to be tied down by this past dogma of neutrality and not wanting to choose a side because of this unwillingness to see the eventual outcome of who is going to win ... whether it's China, whether it's the US.

"And with whoever or whichever side, still we have to face the implications in the future, whether it's positive or negative. So it's important to choose a side.”

He says the easiest way would be to enhance US support by providing facility support for American forces, naval capacity through bases in East Malaysia, and possibly hosting US forces.

“That will be a game changer. When push comes to shove — when the urgency of the threat is really spiralling — this is the easiest, most effective deterrence capacity that we can think of when the stakes are the highest.

"It will really send a strong message to Beijing that it's not too late for the region to stand up to their chessboard manoeuvres.”

In contrast, the Philippines has been a big supporter of the AUKUS presence, with the government two years ago calling for the restoration of "imbalance in forces available to ASEAN member states".

International Development and Security Cooperation resident fellow Joshua Bernard Espéna says Australia’s support for the Philippines has created a foundation for a symbiotic relationship.

“If you would remember, one of the triggering factors as to why the Philippines has supported Australia was that Australia, in itself, supported the 2016 arbitral ruling for many, many years during the Duterte administration,” the foreign policy analyst says.

Espéna is referring to China’s maritime activities in the South China Sea, which the Philippines claimed was a violation of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. In 2013, the nation instituted arbitral proceedings over its respective entitlements at sea.

“[B]ecause of Australia's support to the arbitral ruling in 2020, in which the United States followed suit, it was a comfortable moment for the Philippine foreign policy elites to support anything that would cement their crusade against China's maritime assertiveness. That, in itself, was the motivation of the Philippines, as being supported by external players,” he says.

He argues the AUKUS deal will bring benefits to the Philippines and the rest of the ASEAN members states through a change-up in strategic culture, such as increasing maritime domain awareness and improving naval capabilities.

Importantly, the AUKUS partners need to win the support of Southeast Asia first.

“[AUKUS partners] should look at where commonalities would be, the common concerns, the common spirit, you know, the people-to-people relationships should not be discounted, actually,” he says.

"As much as defence capabilities are required, you also have to power up your diplomacy. Do not approach the great power politics competition like that; address the common concerns, and I think that would be like a bottom-up approach.”

Hudson Institute Asia-Pacific security chair and senior fellow Dr Patrick Cronin says AUKUS partners need to maintain transparency with regional players to ensure regional cooperation.

“In all three countries, I think there needs to also be a greater dialogue with ASEAN institutions to keep ASEAN centrality in terms of the dialogue on these issues, to reassure ASEAN. And as well, the need for some level of strategic dialogue with China, to demonstrate to ASEAN that this is not an aggressive move. This is about defence and deterrence and maintaining the peace so that we can continue to have open trade,” Cronin says.

“I think most importantly that more trade, frankly, and more engagement, multilaterally, will be one of the best support mechanisms for AUKUS, even though it's very indirectly related," he says.

"It will go a long way toward reassuring the region that these submarines are really about preventing conflict and not starting a war.”

AUKUS will begin its first phase of SSN submarine rotations out of Western Australia by 2027, followed by the purchase of three Virginia-class submarines and building a SSN-AUKUS attack submarine by the late 2030s/early 2040s.