Artist challenges 'primitive' attitudes

🔗 [SYSTEM UPDATE] Link found. Timestamp incremented on 2025-11-26 13:55:13.SYBILLA GROSS takes a walk through an exhibition that challenges many of our cultural attitudes.

EXHIBITION

The Right to Offend is Sacred

NGV, March 3 – June 4

By SYBILLA GROSS

The words “KILL PRIMITIVISM” glare in capital pink neon letters over the dark entrance of Brook Andrew's exhibition The Right to Offend is Sacred.

As I enter the first room of the exhibition, I feel enveloped by the darkness. It is marred by a band of neon lighting that lights up the frames on the wall and a scientific glass cabinet stretching the length of the room.

They contain carefully selected clippings from historical archives that focus on colonial history and, with that, the central theme of Andrew's work is set.

Andrew’s modified clippings – all racist, ranging from the subtle to the disgustingly blatant – gently push the viewer towards the idea of doubt and challenge pre-existing notions of so-called “primitivism” as it has been constructed by Western media for centuries.

The archival darkness of the room gives a sense that somehow I am intruding, as if I have walked into a photography darkroom, or, perhaps, as if I am intruding upon an unfamiliar past, conceptualised away from the current dominant discourse on Indigenous history and presented instead as one centred on the Indigenous experience.

In walking through the gallery I begin to feel exclusively privy to an under-reported understanding of history due to the wealth of information available in every small detail of the exhibition.

The detail in each work of art is extraordinary. Andrew's collaboration with Japanese artist Shoichi Kitamura in creating two woodblock prints (Even a failing mind feels the tug of history, 2009, and Legions of war widows face dire need in Iraq, 2009) involves 39 impressions of ink and took six months to complete. The woodblock itself betrays the exceptional level of painstaking effort taken by the artists.

There are many recurring motifs throughout the exhibition. A simple Japanese cigarette box emblazoned with the words "peace" and "hope" tucked away behind a sheet of glass in one room, for example, becomes the centrepiece for an enormous installation in another room (Hope & Peace, 2005).

In the second room of the exhibition, lines of 52 portraits of individuals from 52 distinct Indigenous populations are covered in “diamond” dust.

The choice of diamonds – gemstones of carbon born out of heat, pressure and time – as a transformative medium becomes more artistically appropriate given the large "loudspeaker" centrepiece (Vox: Beyond Tasmania, 2013) in the room seems to optimistically lend the individuals a voice and a new historical narrative of their own.

The red reflection from the walls gives off a more serious undertone of death and destruction, themes which, given their place in colonial history, underscore Andrew's often colourful work.

Many of the pieces are characterised by pop art styles and Indigenous Wiradjuri patterns, an Aboriginal tribe with whom Andrew himself shares heritage.

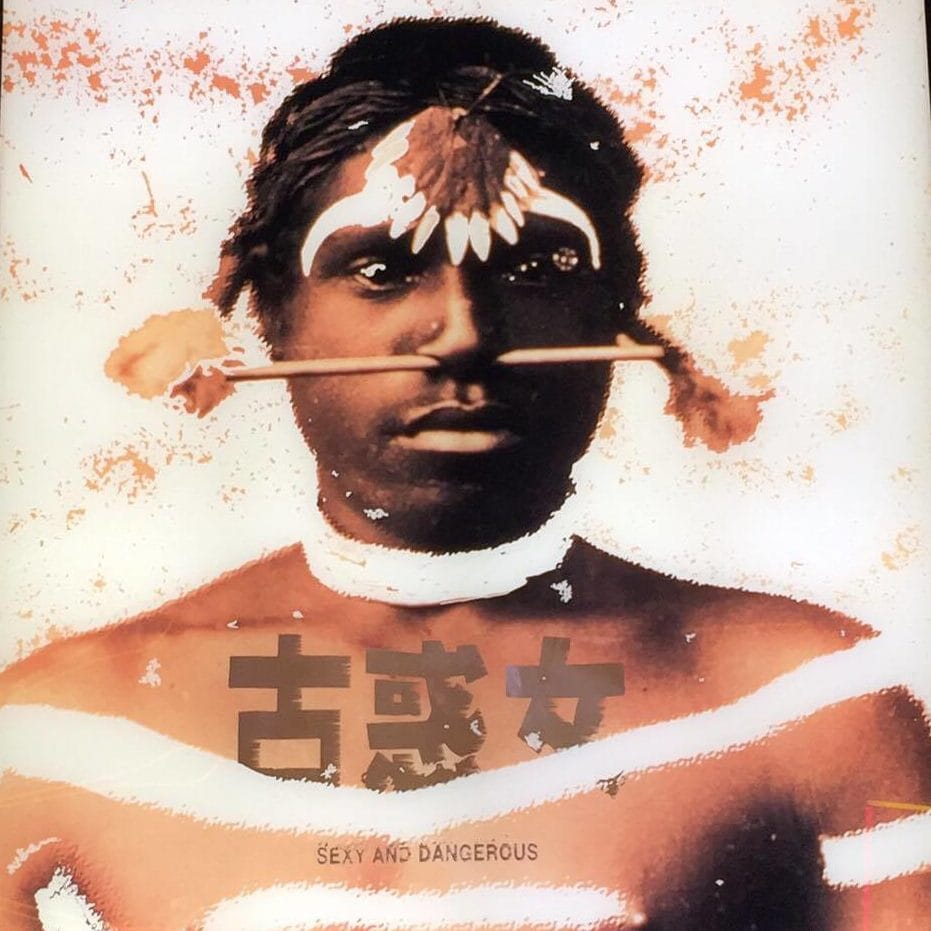

The pop art pays homage to “consumer culture” where acid neon lights seem to sell the idea of the “primitivism myth” by intertwining themselves around black and white ethnographic photographs, creating a shocking contrast.

The idea of “primitivism” as a Western myth is one that Andrew cleverly puts forward through the deconstruction of history and Western understandings of what it is to be “primitive”.

His piece In the Mind of Others (2015) presents a haunting contrast between so-called “primitivism”, understood as a Western construction, and the way in which it has been demonised by the West.

“[The exhibition is] about handing it over to the public and seeing what they do with that information,” Andrew says.

While the multi-disciplinary exhibition touches on some hefty ideas and uncomfortable realities, the experience is an enriching one. This exhibition challenges my perceptions of colonialism and history.

In redefining colonial history and tearing down Western constructions of “primitivism”, Andrew's artistic tone is one of optimism combined with a sense of humour. The name of the exhibition itself plays on Western Voltairean philosophy, which ironically espouses a belief in freedom of speech for all.

Andrew's exhibition is one that takes on the role of actually transferring this traditionally Western freedom to Indigenous culture by reconfiguring history itself.