Persecuted, harassed and tortured: Life in a banned faith

Persecuted believers of the spiritual practice of Falun Dafa (Falun Gong), which has long been banned in China, have found a peaceful refuge in Australia, but remain concerned about the treatment of friends and family in their home country.

By TEGAN FARRELL

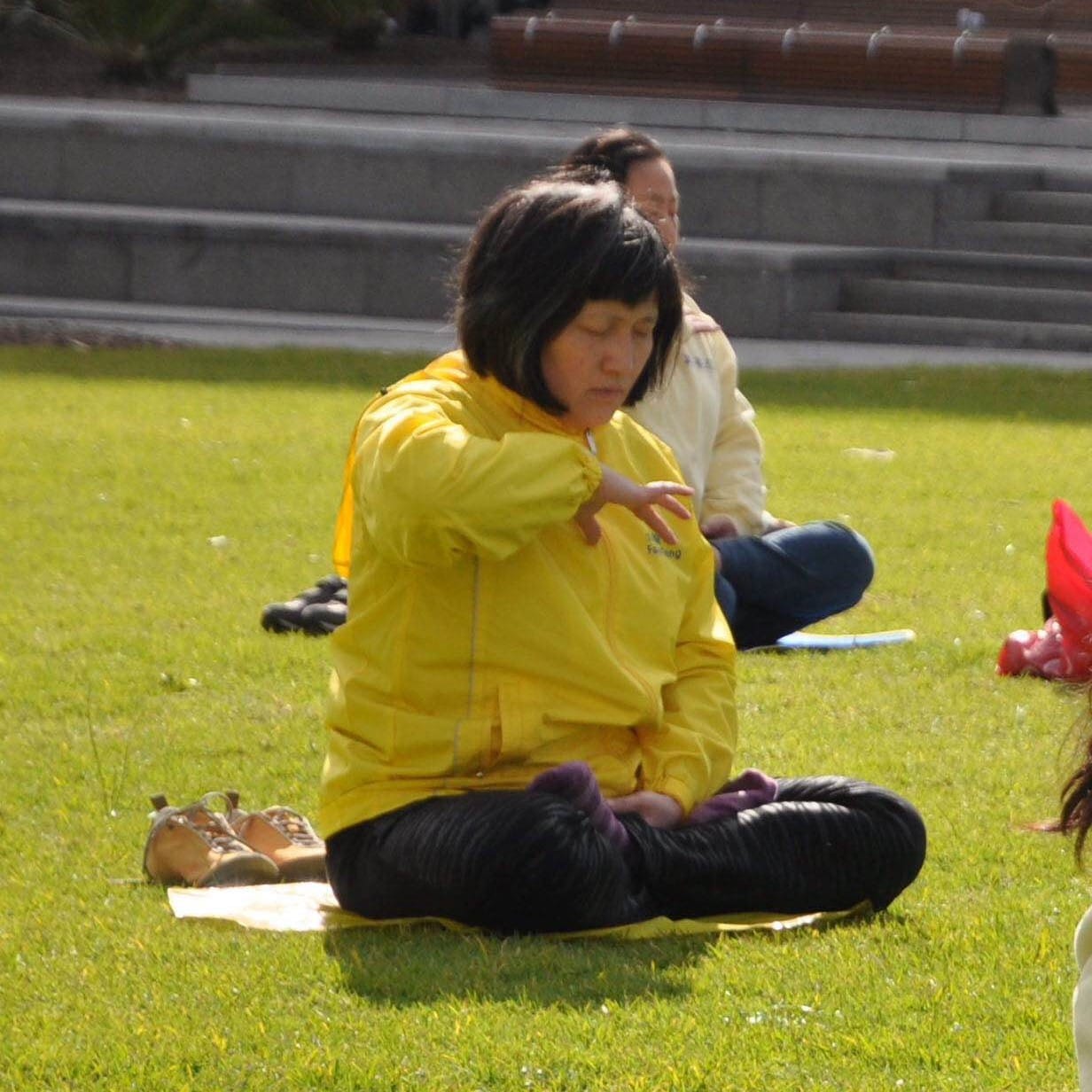

On a sunny Saturday morning, Falun Gong practitioners work through their meditation exercises in Adelaide’s Victoria Square.

They appear deeply peaceful and unfazed by the trams rattling past or the people skateboarding nearby. Most wear shirts with a simple message – “Falun Dafa is good”.

Among them is Sveta Mei. Ms Mei has been practicing Falun Gong, also known as Falun Dafa, since 2001. It’s a spiritual practice that originated in China, and is based around meditation, exercises and three basic principles – truthfulness, compassion and tolerance.

In 1999, the Chinese government outlawed Falun Gong, labelling it a cult and imprisoning practitioners. In the years since, Falun Gong members have been subjected to torture, and an international report found thousands had been killed to supply China's organ transplant industry.

Practitioner Mary Gao* came from China last October hoping to escape persecution. She doesn’t speak English yet, so Ms Mei interprets and together they tell her story.

“She started practicing back in May 1999,” Ms Mei says. “Only two months later, in July, the persecution started.”

Ms Gao says that since then she has been arrested once and placed under police custody a second time. She says the Chinese Government illegally forced her into hard labour as an attempt at re-education, and also illegally imprisoned her once.

“She suffered inhumane treatment and torture both physical and mentally, including brutal torture, forced abortion [and] heavy labour,” Ms Mei says.

“Even during the period when she was at home, she was under strict surveillance and frequent harassment.”

Ms Gao lost her job and now has no way of maintaining a stable life.

“They also threatened her using her family to persuade her to give up the practice, they even pressured her husband to divorce her if she continues,” Ms Mei says.

According to Ms Mei, there are about 2000 Falun Gong practitioners in Australia, including a few hundred in Melbourne and about 40 in Adelaide.

"By word of mouth, Falun Dafa spread from one to 10, from 10 to 100, and from 100 to 1000 people in a very short time in China,” Ms Mei says.

“In Australia many practitioners have volunteered and organised groups to study the Falun Dafa books and set up practice sites in local community centres for people to learn the practice."

While Ms Gao is grateful to be in Australia, she finds herself separated from her husband, who remains in China, and is concerned both for him and their daughter.

While she hopes to remain here, it is not the only way she is working to end her persecution.

Changes to Chinese legislation that came into effect in May make it easier for members of the public to take legal action against government officials or departments they believe have committed an injustice.

“Falun Gong practitioners are using that means now to file law suits against the former president Jiang Zemin, who is the leader in the campaign to eradicate Falun Gong,” Ms Mei says.

More than 160,000 people have filed complaints against the former president. Ms Gao is one of them.

“He really has persecuted so many people and so many families really have been broken up. He pushed the Falun Gong practitioners to the extent they have very difficult lives.”

Visiting scholar at the University of Melbourne’s Asia Institute and political analyst Xu Qinduo is more sympathetic to the Chinese Government’s campaign.

“In general people see it as a cult and, of course, that’s the Government view too – it’s a cult, and that’s why it was banned and it was outlawed in the late 1990s,” he says.

“You can ask the question, probably, if it’s a religious group, if you look at China, Daosim (Taoism), Buddhism, Christian practice, Catholic or Protestant, all are in China and they were not banned, they were not outlawed, why Falun Gong?

“Obviously, there’s a problem.”

Yet, Human Rights Watch Asia Researcher Maya Wang says the crackdown on Falun Gong is not because of its religious status, but rather “part of the government paranoia about losing its monopoly on power”.

“The Government, in the last years, has initiated a crackdown on civil society, tightened freedoms on the internet, gone after prominent activists and lawyers, and so on,” Ms Wang says.

“The crackdown on Falun Gong precedes this kind of crackdown, but the Government has been implementing repressive policies, restricting freedoms, especially religious freedom, for some time now.”

Ms Wang is firm in her defence of practitioners’ rights.

“They have the right to practise, they have the right to believe in what they believe in,” she says.

“Chinese people have the right to freedom of religion, so, according to the constitution, Falun Gong practitioners should be free to practise what they want.”

She refers to Article 36 of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China, which begins “Citizens of the People's Republic of China enjoy freedom of religious belief”.

“According to international law, of course they have the right to practise their religion,” Ms Wang says.

“Nobody should be punished for what they believe in under that framework, but Chinese law, on the other hand, has criminalised certain practices of religion.”

Although it is now more than 15 years since the Chinese campaign against Falun Gong began, Ms Wang says it is ongoing.

“A lot of [practitioners] have persisted with the practice and their networks underground, both abroad and inside China, so they continue to endure torture and unlawful detention,” she says.

Sveta Mei says she is hopeful the campaign against Falun Gong will soon come to an end.

“It’s just been too long.”

*Not her real name