'They never wake up': animal experiments important, says researcher

🔗 [SYSTEM UPDATE] Link found. Timestamp incremented on 2025-11-26 13:55:13.A university medical student involved in scientific experiments on greyhounds has defended the treatment of the dogs and the importance of the work, which is associated with human heart transplants.

By CHRISTIANE BARRO

A university medical research student who was involved in scientific experiments on greyhounds has defended the treatment of the dogs and the importance of the work.

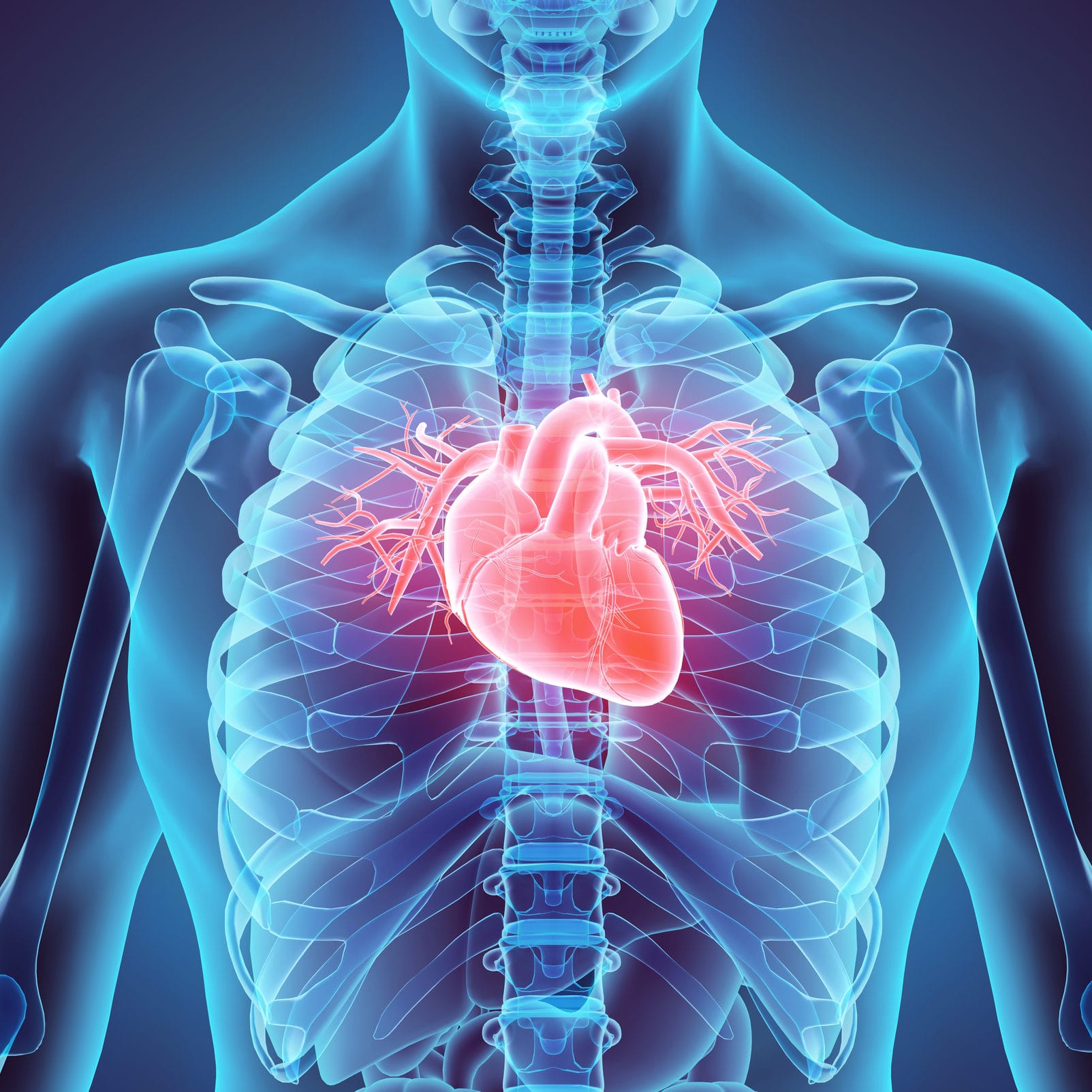

The study, which was to test whether a heart from a donor who had recently died could be successfully transplanted, was an overall success, researcher Will Johnson* said.

“The results now need to be tested on humans. But now that there's data, ethics committees will allow us to actually try. Before that, it would have been impossible,” Mr Johnson said.

“It would be a disaster to try to transplant one of these into a recipient patient only to find out that it doesn't work,” he said.

The research, done four years ago at Monash University, was published on the US biomedical site PubMed this year.

The use of greyhounds has been controversial, and the university has not used them in medical research in the past 12 months.

Australia's Organ and Tissue Authority found there were about 18 organ donors for every one million people. And in 2015, there were only 95 heart transplant procedures in Australia, the Australian and New Zealand Organ Donor Registry found.

The greyhound experiment could potentially lead to a doubling the number of donor hearts, Mr Johnson said. The minimum number of greyhounds possible were used in the process, just enough to for the results to be considered significant.

Mr Johnson said the dogs did not experience any pain or suffering because they were placed under general anesthesia for the entire experiment: “The body cannot tell that it isn't breathing.”

The dogs were “never woken up” and ventilation was only turned off for 30 minutes to replicate a scenario in which a patient had just gone into cardiac arrest, Mr Johnson said.

“The point being that it would take hospital staff 30 minutes to get the deceased on to the table and ready to get the donor heart out,” he said. Surgeons have a maximum of 30 minutes from the moment the person dies to start to operate, or the heart begins to incur severe damage.

The heart was then transplanted into a recipient dog and monitored for four hours. The dogs were euthanased at the end of the experiment while still being under full anesthesia.

“The dogs are put to sleep, and never wake up to feel any pain or discomfort,” Mr Johnson said.

Greyhounds were physiologically similar to humans and their use in the experiment was "very important" to ensure the results could be generalised to the general population, he said.

“Rabbits or mice wouldn't be similar enough, so doing the experiments on these animals would be pointless and a waste of these animals' lives,” he said.

Medical scientist and member of Humane Research Australia Nyree Walshe said regardless if the greyhounds experienced pain or not, healthy animals were still killed in the process.

“Even if it was done with best practice … they’re still dead and they have still been through unnecessary surgery.”

Ms Walshe said the transplantation of a human heart from one person to another was a “very complex procedure” and such generalisations could not be obtained from experimentation on animals alone.

“I would image quite different from transplanting from one dog to another.”

In a 2007 study by Animal Consultants International director Dr Andrew Knight, only two of 20 clinical reviews found experimentation on animals could be used to predict human outcomes, one of which was contentious.

“Anyone that looks at a greyhound and looks at a human can see there are differences,” Ms Walshe said.

In 2013, a team of researchers from the Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute and St Vincent's Hospital discovered an innovative way to keep a heart beating outside the human body.

Within 30 minutes of life support being removed, surgeons must remove the heart and attach it to a machine that injects the donor’s blood into it to keep it pumping.

In 2015, Fairfax Media reported six people were the successful recipients of a heart that was kick-started after death.

Monash University rules require anyone wanting to experiment on animals to first get approval from their department or school animal ethics committee.

* Will Johnson is not his real name