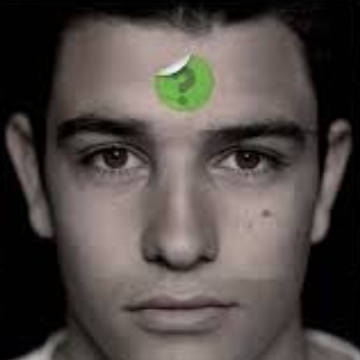

Why it matters: intervening in youth mental health

The biggest killer for Australian youth today is suicide. On RUOK? Day, DAVID BULAFKIN looks at the national mental health service headspace and how it tries to help young people cope.

By DAVID BULAFKIN

The facts are staggering: One in five Australians will experience a mental health issue in their lifetime. Less than half of those people will actually get help. The biggest killer for Australian youth today is suicide.

And behind these figures it's important to remember: Each of these numbers is a person.

Anita Gurrieri is one of thousands of Australian youths today experiencing a mental health problem.

Ms Gurrieri is a bubbly, brash 22-year-old whose zest for life is contagious. She’s someone who walks into a room and demands attention, with her dyed hair and zany but beautifully manicured flower headpieces, matched with enchanting stone necklaces.

We’re sitting in an offensively bright green room at headspace Bentleigh, after the launch of the organisation's newest initiative: the Youth Early Psychosis Program (YEPP).

Headspace is a national youth mental health organisation, offering a range of services to people aged 12-25.

The new program – YEPP – aims to intervene at the earliest possible stages of psychosis. This is done through youth engagement, targeting at-risk individuals in an effort to reduce or stop psychosis from developing.

Ms Gurrieri said she would have benefited if this program had been available to her.

“When my psychosis happened, we didn’t know what was going on – no one in my family had anything like this happen to them,” she said.

Ms Gurrieri said headspace had been a lifeline for her.

“[It’s] a wonderful support system – people that care and want to help you.”

In 2014 the Federal Government held a review on the mental health system in an attempt to reshape the current framework, which is costing taxpayers $10 billion annually. The report was published in April, with the Government saying it was setting up a reference group to respond to its recommendations.

There are more than 80 headspace centres around the country and the Australian Government has confirmed funding for 100 centres to 2016. The funding will be fixed, and not indexed.

The review raised the issues of access to services, and those services adequately catering to individual groups. Headspace was acknowledged as an important service, but was also described as "overly centralised".

Headspace CEO Chris Tanti said accessibility was the highest priority. “There’s a whole lot of people out there who don’t get help,” he says.

“The more we raise awareness around this issue, the more that people can come forward.”

Stigmatisation, minimal funding for what is an enormous sector and difficulties accessing services for people in lower socio-economic groups all diminish the effectiveness of the mental health system.

To overcome this, headspace attempts to create inviting, youth-centric spaces. The initiative also caters to rural and remote areas through mobile service teams.

National Mental Health Commission CEO David Butt said in a press release at the launch of the review's findings, that things needed to change.

“[The] current system is not designed with the needs of people and families at its core … navigating the mental health system is complex and difficult, meaning people are unable to access the support and services they need.”

Mr Tanti acknowledged the significance and relevance of the review, and agreed with shifting the focus from acute hospital services to community-based care.

But he was concerned the funding freeze would result in job cuts.

Another difficulty is tracking the system’s performance, with current indicators based on numbers and dollars.

Opposition youth affairs spokeswoman Steph Ryan said the figures were sometimes arbitrary.

“I think one of the problems politicians make is they tell people what’s good for them rather than asking them what they need,” she said.

Alfred Health’s Child and Youth Mental Health Service manager Glenda Pedwell said a funding boost for mental health was desperately needed.

“It’s a pretty poor cousin to the other health sectors. We’re in a situation where people are fighting for scarce resources in a system that’s stretched to the max.”

Organisations such as beyondblue and events such as R U OK? Day are attempting to reduce the stigma around mental health.

With programs like YEPP, young people like Ms Gurrieri have the best opportunity to acknowledge and overcome these challenges.

“ 'It’s normal if you’re feeling like this' or 'This is happening to you' would have been really helpful for me to hear,” said Ms Gurrieri. “ 'You’re not a freak. You’re not a weirdo. You’re just experiencing things a little differently and that’s ok.' ”

Readers seeking support can contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or visit your local headspace centre which can be found here.

David Bulafkin is a headspace volunteer.