Exploited and unheard: Suicide among Indian farmers

Suicide rates among farmers in India are often described as epidemic but some of the issues are similar to those Australian farmers face. BY KIRSTI WEISZ When an Indian farmer commits suicide, there’s a high chance he comes from the dusty, arid...

Suicide rates among farmers in India are often described as epidemic but some of the issues are similar to those Australian farmers face.

BY KIRSTI WEISZ

When an Indian farmer commits suicide, there’s a high chance he comes from the dusty, arid state of Karnataka, located in India’s south.

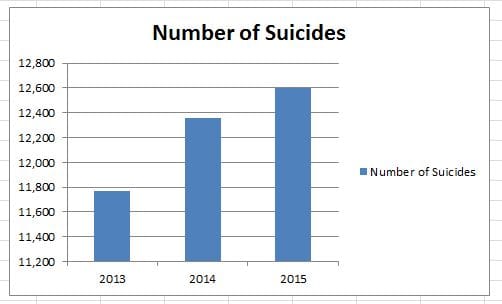

According to India’s National Crime Records Bureau, Karnataka has one of the highest suicide rates across the country and accounted for 38 per cent of total farmer suicides in 2015.

Just over 7000 kilometres away, in the dry, remote farms of inland Queensland, Australian farmers have access to far better technology and agricultural products than their Indian counterparts.

But these farmers share an unusual connection with those in Karnataka. Queensland farmers are also more likely to commit suicide.

Dr Siddhartha Mitra, an economics professor from Jadavpur University in India, published a study in 2006 comparing the farmer suicide rates between Australia and India.

He was surprised to find high suicide rates across two countries with different populations and agricultural practices.

“The finding that high suicide rates can occur in countries characterised by advanced agriculture practices … as much as they can occur in countries with relatively primitive and labour intensive agriculture … is itself a surprising finding,” he says.

“This implies that modernisation alone cannot solve the problems of the farming community. A more nuanced approach is required.”

In Nagnur, a small village located in Karnataka, the men’s self-help group says villages nearby have suffered from farmer suicides.

“We have never faced suicide problems but surrounding villages have,” says Mr Muthanna Hadpad, the group’s leader.

“It’s better [for us] compared to the other villages. Not so good, but not so bad.”

Similar to the effect of droughts in Australia, the men’s self-help group, which consists entirely of farmers, listed the lack of water as a main issue they face.

“The major problem we are facing is rain because there is not a good amount of rain here,” Mr Hadpad says.

“That is a natural process, we can’t force that.”

Bankruptcy and indebtedness are another reason behind the high suicide rates in both countries.

In India, this was a significant cause of farmer suicide in 2015, contributing to 79 per cent of the farmer suicides in Karnataka alone.

The men’s self-help group says the difficulty repaying loans and a lack of profit they make on produce are reasons farmers in the area commit suicide.

“The major reason here is the loan that we cannot pay back and the other reason is the money we invest in the crops, we do not get the same money back.”

“When we take the loan we get 50,000 rupees [approximately $AUD 980] in our hands, we will be very happy but when it comes to paying it back we [have] difficulties…

“We cannot spend it on something else we want for our homes. It just comes from the field and goes to the field,” Mr Hadpad says.

Since the 1960s, farmers have been required to sell their produce to the Agricultural Produce Market Committee so that they would receive fair prices and not be exploited in trade.

However, Indian freelance journalist Nikitha Sattiraju, who often reports on agriculture, says the legislation establishing the committee has “failed to shield the farmers from exploitation”.

“Today, middlemen and intermediaries, in collusion with committee officials … exploit the loopholes in the act and procure produce from farmers at low prices and sell to consumers at far higher rates,” she says.

“No matter how high the market prices are, farmers never benefit from it.”

Ms Sattiraju also says the cost of production is steadily rising while the return for farmers is varied. Since banks need collateral which farmers’ do not have, Ms Sattiraju says villagers often turn to money lenders who are “exploitative and slap exorbitant interest [rates] on the loans”.

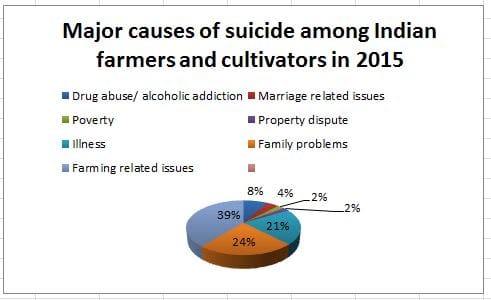

“The inability to cope with mounting debt is why a majority of [farmers] end their lives… it doesn’t necessarily have to be agricultural related debt, it can be because of loans taken out for marriages as well,” she says.

“But no matter the reason behind the loan, it is the standard of living owing to the poor state of their occupational sector that pushes them into a vicious cycle of borrowing.”

Families of a farmer who has committed suicide can receive up to 500,000 rupees (approximately $AUD 9,700) compensation from the government.

However, the payment can be denied if the farmer does not own their land and there may be a delay in receiving it.

“The monetary relief, if the families manage to get it, isn’t of much help beyond clearing the debt (or just a part of it) left behind by the farmers,” Ms Sattiraju says.

“This manner of relief is not the solution. In fact, in some cases, it can even be seen as abetting farm suicides because farmers kill themselves so their families can get the compensation.”

The rate of suicide among farmers is higher compared to other occupations across the world. Studies in Sri Lanka, the US, Canada and England have found farming to be one of the most dangerous industries.

In Australia, Dr Kennedy from Deakin University and the National Centre for Farmer Health is working with other researchers to better understand the impact suicide has on the farming community.

Dr Kennedy says there is a lack of funding, understanding and resources to combat suicide in Australia’s rural communities. That is why the Ripple Effect website was launched last year for farmers to anonymously share their stories.

“People need to understand that the risks, protective factors and tipping points for suicide can be different depending on the context …

“A deep understanding of rural farming life is needed before effective responses can be developed. Hence the need for the Ripple Effect,” she says.

In India, Ms Sattiraju is losing hope that the high number of suicides can be reduced.

“The situation hasn’t improved in over two decades and I honestly do not see it getting any better soon,” she says.

“Public investment, technological progress, guaranteed returns, farmer awareness and crackdown on corruption – all of this and more is necessary to tackle the multifold issues that affect the country’s agricultural system.

“It is a mammoth task and considering the complacency of previous governments and the present one towards the crisis faced by the farm community, the future doesn’t seem reassuring.”

Australian mental health support:

Lifeline 131 114

Beyondblue 1300 224 636

Suicide Call Back Service 1300 659 467