India’s government education still not passing the test

BY JAYITRI SMILES Father of four, Balu Ningrani, noticed something peculiar about his youngest and eldest child. Despite only being three years old, his son already understands English at the same proficiency as his seven-year-old daughter. Mr...

BY JAYITRI SMILES

Father of four, Balu Ningrani, noticed something peculiar about his youngest and eldest child. Despite only being three years old, his son already understands English at the same proficiency as his seven-year-old daughter.

Mr Ningrani’s son attends a private kindergarten, while his daughter is enrolled at a local government school.

After enrolling his two youngest children in the non-government system, Mr Ningrani says he realised there is a clear difference in quality between private and public institutions.

“There is a lot of ignorance in government schools and the teachers are rarely of good quality,” says Mr Ningrani.

“Teachers are there for job security and government salary while children go to eat their free meals and sleep,”

“Private schools are more organised, they give homework, the teachers are better and English is the medium of communication,” he says.

While India has an official primary school enrolment rate of 98.5 per cent, the inconsistent quality of government education means some children are being left behind.

The Australia Council for Educational Research (ACER) India identifies unpredictable standards and attendance as major issues of the country’s system.

“India has an enormous school sector with significant variations in quality across schools…. there are some outstanding government schools and there are some terrible ones,” says ACER India research director Sarah Richardson.

“There are schools where children sit on the ground, there are next to no learning materials and there may be only one teacher to deal with a large multi-level class.”

The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2013 says only 47 per cent of fifth grade students can read books at a second grade level.

Despite nearly 100 per cent enrolment, ASER also reports that only 70 per cent of students attend school on any given day.

“Attendance is a real challenge in many Indian schools, particularly as a result of children needing to assist with family responsibilities, farming work or to earn a wage to support other family members,” says Ms Richardson.

A recent ASER publication also shows the results of rural students enrolled in public schools are significantly worse than their non-government counterparts.

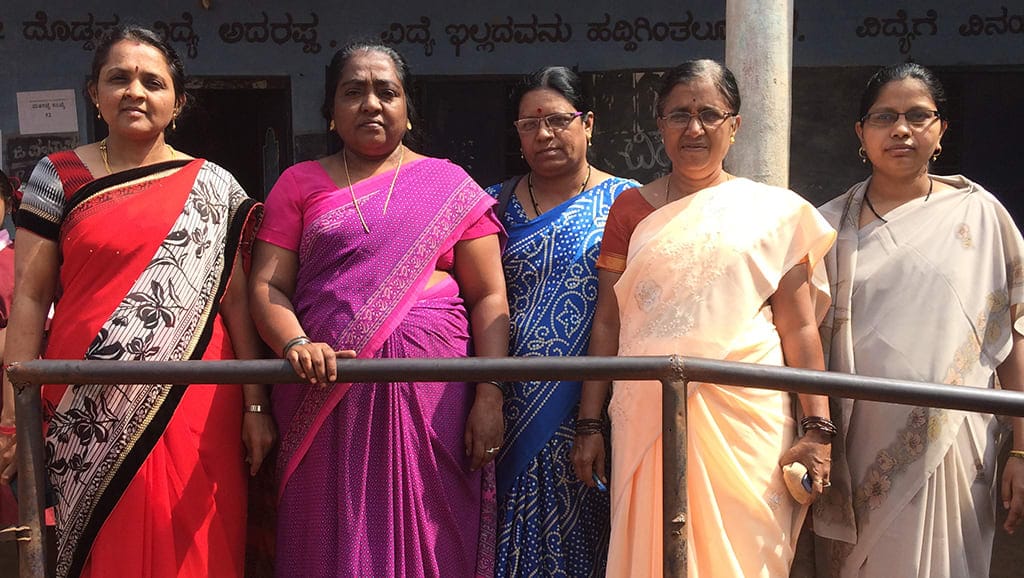

In rural areas of the south Indian state of Karnartaka, teachers at Soorshetti Koppa’s public school say they feel let down by government funding in training and facility upgrades.

Mrs Shakuntala Navalagud, a teacher at HPS Soorshetti Koppa, says all instructors have two years of training with no specific focus on teaching maths or science. They have trouble controlling large numbers of children in run down classrooms.

“The government provides free midday meals and uniform, but doesn’t care for the buildings. We rely on parents and ourselves for maintenance,” says Mrs Navalagud.

A number of not-for-profit organisations operate their own schools in India to provide disadvantaged children with a better education. These institutions typically welcome children whose families’ could otherwise not afford private school.

Adam Woodward, director of the not-for-profit school Kalkeri Sangeet Vidyalaya (KSV) in Karnataka says his educational institution follows the state syllabus but re-train teachers.

“Government school teachers are very authoritarian with high discipline, which is comparable to other kinds of institutions like prisons,” he says.

“Currently, non-government schools are doing a much better job at breaking the cycle of systemic poverty.”

Unlike government schools, not-for-profit educational institutions like KSV, the Yatra Foundation and Pratham are focusing on breaking down rote learning. Instead, an innovative and hands-on method of teaching is used.

Despite these setbacks, India’s national government continues to push for an educated future generation. A successful midday meal program is improving attendance and school has been free of charge for children between ages six and 14 since 2009.

The government also created financial incentive schemes to ensure girls are encouraged to study as much as boys.

The Bhagyalakshmi scheme in Karnataka – which provides female high school graduates with 35,000 rupees – convinced Mr Ningrani to keep his eldest daughter enrolled in public school.

The government lets families spend accrued money on their daughter’s marriage or higher education. For Mr Ningrani, the choice is simple.

“My daughter struggles in comparison to my children at private school but I hope the opportunity to send her to university will make up for this.”

[Feature photo used under creative commons.]