The journey towards a cashless society: India’s demonetisation explained

BY STEPHANIE CHEN On November 8 last year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi sent the Indian population into frenzy when he announced all 500 and 1000 rupees notes would become redundant at midnight. Within a week, Indian newspapers had reported over 30...

BY STEPHANIE CHEN

On November 8 last year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi sent the Indian population into frenzy when he announced all 500 and 1000 rupees notes would become redundant at midnight.

Within a week, Indian newspapers had reported over 30 deaths as a result of the demonetisation.

There were reports of suicides, people dying in long lines while waiting for bank services and the refusal of medical assistance to those who did not have valid denominations.

Professor of economics at Jadavpur University, Siddhartha Mitra, said those living below the poverty line bore the brunt of Mr Modi’s decision.

“The poor were adversely affected to the largest extent and the adverse effects weakened as you moved up the income ladder,” said Mr Mitra.

The Indian government argues that its demonetisation policy will fight corruption, crime and tax evasion by curbing the population’s reliance on paper money.

It also maintains the two monetary notes in question – 500 and 1000 rupees – had become easy to counterfeit.

But the sudden move had serious consequences for local economies.

Small businesses and rural economies went broke, as they had relied heavily on the demonetised notes to pay their workers and conduct their trade.

The elected head of village Niv Je in Maharashtra, Mahendra Shyam Pingulkar, said while his people were able to get by, they had run out of money for normal trading activities.

“We had to rely on favours when there was not enough cash to pay with and remember to pay people back for favours when we would finally receive the notes we needed,” Mr Pingulkar said.

The notes Mr Modi decommissioned made up 86 per cent of the cash in circulation in a country where it is estimated that 90-98 per cent of transactions involve cash.

Mr Mitra said because the notes were widely used, demonetisation had caused “massive recessions” in parts of the Indian economy.

“The informal sector, which houses most of the poor people in the economy, trades almost entirely in cash,” Mr Mitra said.

“Demonetisation, by creating a shortage of currency, resulted in a severe [shrinkage] of monetary transactions in the informal sector.”

In an article for the Financial Times, Professor of Economics at Harvard University, Kenneth Rogoff, estimated that demonetisation will reduce gross domestic product growth by one or two per cent.

“There may be significant long-term benefits to Mr Modi’s radical policy [but] the short term results have been catastrophic… with those on lower and middle incomes and the poor bearing a particularly heavy burden,” Mr Rogoff said.

Mr Rogoff also said the situation was worsened by a lack of preparation. The Reserve Bank of India had not printed enough replacement notes and despite Mr Modi’s best efforts, the use of electronic payment methods were still relatively uncommon.

“Developing economies probably should not think about phasing out cash until they have sufficient electronic payment infrastructure,” Mr Rogoff said.

“[In India] well over half have not yet set up accounts, even if they are now rushing to do so.”

Mr Modi gave an emotional response to the backlash by asking the Indian people to push through the “pain” and trust his decision.

“I have only asked for 50 days… After that, if any fault is found in my intentions or my actions, I am willing to suffer any punishment from you,” Mr Modi said

While Mr Mitra acknowledged Mr Modi’s objectives in tackling corruption and crime were noble, he believes the radical move was likely a political stunt.

Mr Mitra argues other policies would have better targeted these issues and would have better suited India’s economic environment.

“[The government could have] placed upper limits on cash withdrawals and then lowered these limits over time to encourage less cash intensive economic behaviour… [Or] eyeball suspicious asset consumption in large and medium sized cities to detect mismatches between declared incomes and newly owned assets,” Mr Mitra said.

Mr Mitra and his colleagues have also written an open letter to Mr Modi with new policy recommendations that would “bring the informal sector back on track”.

A move towards a cashless society

Despite the collateral damage and international critique, Mr Modi announced in his monthly November address, his hopes for India to become a cashless society.

Mr Modi urged the Indian population to view demonetisation of 500 and 1000 rupee notes as an opportunity to embrace digital forms of payments.

“I want to tell my small merchant brothers and sisters, this is the chance for you to enter the digital world,” Mr Modi said

“We can gradually move from a less cash society to a cashless society.”

A branch manager at the Bank of India, Ravi Pawar*, said although the road to a cashless society would be long and difficult, there would be benefits worth fighting for.

“After another five years, I estimate a 10 per cent economic growth for India due to demonetisation,” Mr Pawar said.

“Also tax, only three per cent of Indians are being taxed by income tax. If we can keep track of income through electronic payments and even if only 20 per cent of Indians pay income tax, then the government will have huge amounts of money to use.”

Mr Pawar said he is already seeing a growth in bank accounts being created and is hopeful about India becoming a cashless society.

“People are now scared to store lots of money in their houses because of the 500 and 1000 rupee cancellation. They’re worried something like that could happen again and so they are putting their money in bank accounts,” he said.

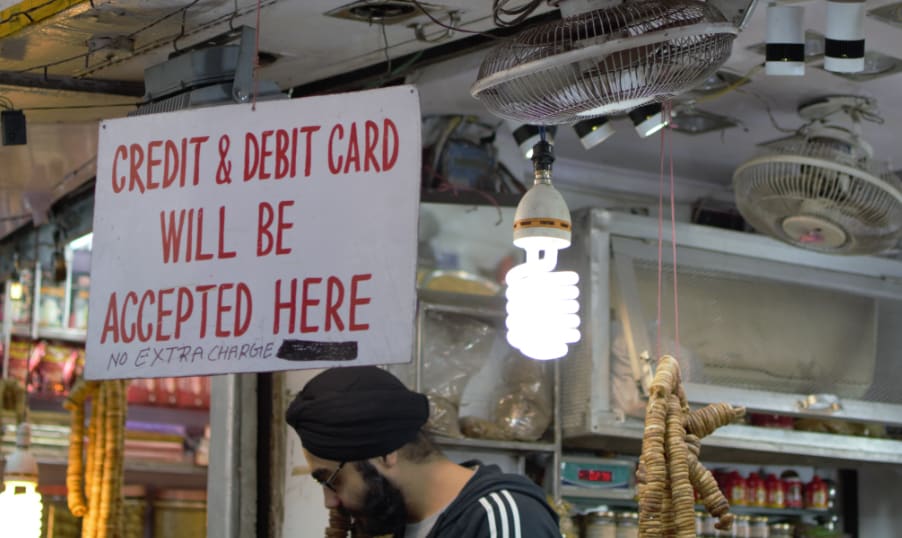

Despite this, spice market stall owner, Darpan Chaudhary* finds it difficult to believe Indians will desert cash for electronic payment methods anytime soon.

“There’s not even more demand for electronic payments, even after the demonetisation, in fact I would say people want cash even more now,” Mr Chaudhary said.

“I’m one of the only stalls in this whole market, if not the only one, who even offer electronic payment options.

“I support it and the young people might support it but … the main business [everyone here] believes in cash.

“I don’t think India can ever become cashless.”

*Names have been altered.

[Interviews with Mahendra Shyam Pingulkar conducted via translator.]