ECT: shock treatment given OK for young children

Electroconvulsive therapy is gentler and more effective than people might think, according to the psychiatrists who believe it is an essential weapon to fight deep depression. Under new mental health laws, it can still be used on young children...

Electroconvulsive therapy is gentler and more effective than people might think, according to the psychiatrists who believe it is an essential weapon to fight deep depression. Under new mental health laws, it can still be used on young children.

By AMY-ANN RUCK

New mental health laws that came into effect on July 1 in Victoria permit electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) to be used on children under 12, despite a chorus of community objections.

The Mental Health Act 2014 will impose stricter safeguards on the procedure, but stopped short of banning it for young children.

Forensic psychiatrist Professor Paul Mullen, a former clinical director of Thomas Embling Hospital, said the issue was a difficult one, but he did not agree with the decision.

“I find it difficult to believe that there would be a justification for using ECT in children under 12,” Prof Mullen said.

“When I started in psychiatry, ECT was administered in a way and for reasons which I found distressing and unacceptable, and I never really changed my views on that,” he said.

The state Leader of the Opposition, Daniel Andrews, agreed.

“It is very difficult for us to contemplate and provide for a circumstance where a child under the age of 12 years could need and then be administered electroconvulsive treatment in involuntary circumstances. That is a very challenging concept to come to terms with,” he told Parliament.

The new laws were, however, supported by many mental health professionals, including the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP).

The process should only be used as a last resort, but could be a life-saver, the organisation said in its submission to Parliament on the issue.

“The denial of emergency ECT treatment for adolescents ... [would be] unconscionable, discriminatory, and could result in preventable deaths,” it said.

According to the Victorian Chief Psychiatrist’s annual report In 2010-2011, 1688 people were given ECT, of which 35 per cent were involuntary. The youngest were three teenagers aged 17. In 2012-13, two adolescents, one aged 15 and one 17, received ECT treatments.

Under the previous legislation, which has been in place for nearly 30 years until July this year, involuntary ECT required the approval of a second psychiatrist.

Under the new laws, a mental health tribunal has been given responsibility. Three tribunal members – a legal member, a psychiatrist and a community member – have to approve any application for involuntary and underage ECT treatments.

The family must also be consulted and the patient has a right to a review and an appeal.

What happens in ECT

ECT has come a long way since its early application in the 1930s and ’40s when it was known as electric shock therapy.

Professor of Psychiatry at St Vincent's Hospital Professor David Castle said the modern procedure was safe and done under the effect of a muscle relaxant and anaesthetic.

“You’re not awake during the procedure; you don’t shake around like you see in One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest or anything like that,” he said. Prof Castle is also chair of the Victorian Branch of the RANZCP.

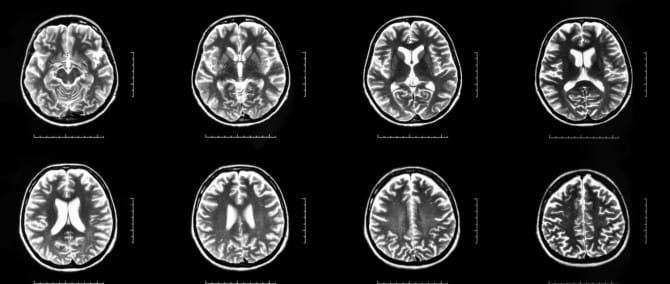

Electrodes are placed on either one side (unilateral) or both sides (bilateral) of the head. A current is passed through the brain, which induces a seizure. Prof Castle said the unilateral treatment, called ultra brief, reduced the potential for memory loss and brain damage, which were known side-effects of treatment.

University of Adelaide medical student Laura Deveson said she was expecting something traumatic when she witnessed an ECT procedure, and was startled by how little reaction there was.

“The reaction on the body was all so tiny we wondered … Is that it? Is it done?” she said. “Just watching for the curl of the toes, that’s about as much as you see in the whole body.”

Pluses and minuses of treatment

ECT is usually prescribed for people with severe depression who have not responded to medication.

The deputy director of Monash Alfred Psychiatry Research Centre Professor Paul Fitzgerald said the decision to use ECT was about balance.

It was important to remember that depression was very disabling and could be “a danger in itself”, he said.

“It should be used as an intervention only if there are no other options, as a last resort.”

Prof Mullen agreed ECT could be less dangerous than other options.

“For most people, you’re probably somewhat safer with ECT than the higher doses of anti-depressants ... I understand completely the repugnance for ECT at a sort of gut level, but the fact of the matter is the evidence for its use is overwhelming.”

While he objected to its use on children aged under 12, he said this was not his area of expertise.

“For some patients, unless you use ECT they are going to remain severely depressed probably for the rest of their lives,” he said.

Prof Fitzgerald said ECT had significant side-effects, but was an essential tool.

“I think ECT should be done with consent, but if a patient is so severely depressed ... and cannot give consent, then an involuntary ECT is likely to save lives,” he said.

For children, he said it should happen “rarely and with great caution”. “It should be used as an intervention only if there are no other options, as a last resort.”

Prof Castle also said it was an essential tool that was closely regulated under the new Act, with substantial safeguards.

“It can be lifesaving. Some young people have had benefits, certainly there is literature about that.

“It is used very rarely and certainly we would be very judicious about it and very careful about it and try to involve family and parents in the decisions around these things, but I don’t think prohibition is the way to go.”

Mixed response from patients

Some of those who’ve had ECT found it helped, but others are less positive. Several have posted their views in online forums on the issue.

On a forum on www.depression.about.com in November 2013, former patient Kat counselled against it.

“I had ECT almost 3 years ago. It destroyed me,” she wrote. “ECT is like playing Russian Roulette ... I know ECT has helped people. But at the same time it has absolutely destroyed the lives of so very many people.”

Dee added in March 2014: “Don’t go for ECT treatments. They erased my past, destroyed my cognitive ability and left me still depressed with no reason to go on.”

Others found it helpful. Juliet, a beyond blue forum board user, had at least 12 treatments at the Perth Clinic. After her ninth, she wrote, she started to feel better.

“I have been finding that forgetting a couple of things here and there doesn't really matter that much! To me, anything is worth feeling this good!! I currently feel 100% better.”

She said she “would have no hesitation in undergoing more treatments in the future” if she became depressed again.

Prof Castle said the treatment wasn’t universal. “Nothing works for everyone,” he said.

“I’ve seen it completely turn people around and get them back functioning adequately.

“If I had a severe depression which wasn’t getting better on medication I would certainly have ECT,” he said.

The role of the new tribunal and laws

Prof Fitzgerald said he was concerned the new mental health tribunal, which will decide all cases of involuntary ECT treatment, might not meet the urgency required for approvals.

“Patients are in extreme danger from hurting themselves and or others. The approval is necessary in a very brief period of time for severely ill patients,” he said.

ECT will be dealt with by a separate section of the tribunal, with its own priority system, which will allow ECT cases to be dealt with quickly.

Prof Castle said increased paperwork and the administrative burden associated with tribunal hearings was time-consuming and was “the responsibility of senior medical staff – one of the scarcest resources within the mental health system”.

“Potentially 30 per cent of consultant and senior registrars’ time will be taken up with the new Act. That’s not bad in itself but it means that’s 30 per cent less time for direct patient care.

“We will need to monitor this very closely and carefully.”

Manager of the Legal and Policy Unit at the Department of Health Emma Montgomery said other states already had a tribunal system and “the sky hasn’t fallen in”.

Ms Montgomery said the predicted caseload increase was 25 per cent, rising from 6000 cases a year to 8000. That worked out to be just over one case more per week for every public mental health service in Victoria.

“Paperwork empowers clinicians, without it, it would be assault .... if a clinician treats someone without it, it makes them liable, it protects the patient and the clinician.

“We know it changes things, but we are investing $84 million recurrently to health services to cover the increase.”

The new tribunal replaces the former Mental Health Review Board and Psychosurgery Review Board of Victoria.

People seeking support and information about suicide prevention can contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Suicide Call Back Service 1300 659 467 or follow @LifelineAust @OntheLineAus @kidshelp @beyondblue @headspace_aus @ReachOut_AUS on Twitter.

See other stories in mojo's series on mental health:

Suicide in custody sparks push for change

Mental health: Lack of support pushes fragile parents to the limit