Nepal’s Himalayas feel the heat of climate change

When Nepal's big mountains are no longer smothered in snow and the glaciers are collapsing, locals know something disastrous is happening to their climate.

By CHLOE STRAHAN

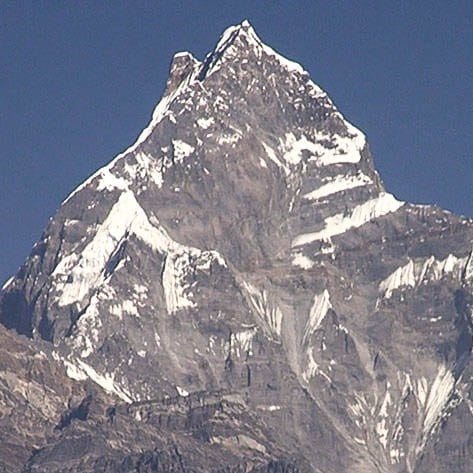

Sita Rai, a trekking guide, gazes at Nepal’s Machapuchare mountain with a look of both awe and sadness.

The sacred mountain towers above the small village of Lwang, near Pokhara, where Ms Rai brings foreign tourists as part of her trekking tours.

She remembers when Machapuchare was covered in snow. Now all she can see is black rock.

“I know mountains, I have been on the same mountains many times,” she says.

“I have seen 10 years ago that there was a big glacier. I keep watching that glacier every time I go to the Annapurna South trek.

“Now half of the glacier is gone, you can see half of the rock.”

Ms Rai has been a trekking guide with 3 Sisters Adventure Trekking for 15 years, frequenting the Annapurna base camp (4130m), Mardi Himal mountain (4200m) and the Hiunchuli mountain (6441m).

She says that in December there should be rain and snow on these mountains.

“I don’t have a photo, but I remember it. Annapurna south and Hiunchuli was full of snow.”

Machapuchare, or “Fishtail” mountain, during the winter season of 2016-17. There is a noticeable lack of snow. Picture: Chloe Strahan.

The world pollutes; Nepal suffers

People living in Nepal rely on the Himalayan mountain ranges to survive. Agriculture, water and tourism are all linked to these mountains, but the consequences of climate change is altering the livelihood of the Nepalese people.

Dr Martin Rice, head of research for The Climate Council, has researched the impacts of climate change in Nepal.

He says that the main consequence is an increase in global temperature, which is primarily driven by the human activity of burning fossil fuels: gas, oil and coal.

Last year was the hottest on record since 1880, making it the third year in a row to set a new record for global average surface temperatures.

“Nepal is hugely reliant on forestry, agriculture and tourism, yet these are highly climate sensitive industries so there are major pressures on these sectors for climate change, and that obviously impacts livelihoods in Nepal,” said Dr Rice.

“There have been studies that estimate that we’re seeing a 75 per cent faster rate of temperature increase above 4000m, and many of Nepal’s mountain regions are well and truly above that.”

Machapuchare, or “Fishtail” mountain, is 6993m high.

The rising temperatures in Nepal’s mountain ranges means that there is a decrease in snow cover.

Dr Rice says snow’s white surface reflects solar radiation, but if there is no snow then the sun will fall on a darker surface. This will heat up the mountain surface, therefore increasing the temperature in the air.

A woman from Lwang village farms potatoes. Picture: Chloe Strahan.

Effects on agriculture

A decrease in snow cover on the Himalayan mountains is detrimental for the livelihood of the Nepalese people, as the changing weather conditions affect agriculture.

Pyare Gurung is the leader of the mothers group in Lwang village. She is concerned that it has not rained yet this winter, saying that rain is important for farming.

“Years ago there was rain in the winter and then we could farm mustard, potatoes and barley. Nowadays nobody can farm mustard or barley, because there is no rain,” says Ms Gurung.

Locals in Lwang village are struggling to grow their crops, noticing that the winter is warmer than previous years.

Three women, Dilkuri, Purna and Assa, from the Pariya caste in Lwang, spend their days carrying food and building supplies on their backs. They do not know what global warming is, but they can see how the lack of rain is affecting farming in the village.

“If there is snow then we can get water from the mountain and put it through the irrigation system so we can farm,” said one of the Pariya women.

“If there is no snow on the mountain, then there is no water, then you cannot grow things.”

The unseasonable warmth during Nepal’s winter months also has trekking guides such as Ms Rai concerned.

“I am sad because we cannot grow winter crops like barley, wheat or potatoes in some places. Some people plant already but the plants cannot grow, there is too much sun,” says Ms Rai.

The women of Lwang village have noticed a lack of rain and snow in recent years. Picture: Chloe Strahan.

More natural disasters

There are other risks to Nepali livelihood due to temperature increases, according to Dr Rice. Incidents known as glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs) are one of the biggest threats to life in Nepal.

Melted snow as a result of climate change can collect in hollows on the mountains, forming glacial lakes.

“When we get intense rainfall or a destabilisation of the ground because of an earthquake, then these lakes can burst and they just funnel through valleys,” said Dr Rice.

“Sadly there’s been hundreds of loss of life in Nepal through well over 20 GLOFs.”

Glaciers are known as the water towers for South Asian countries. Dr Rice says that as climate change continues to melt the snow, there will be an initial rise in water availability.

But as the population grows, there will be a significant reduction of water availability towards the end of the century.

Climate change can also have indirect consequences to earthquakes in Nepal.

Dr Rice says forestry provides a natural buffer for avalanches during an earthquake, and people rely on forests for firewood and shelter.

If intense rainfall occurs in a deforested area, the soil on the mountain can be destabilised. An earthquake can disrupt the unstable soil, creating a landslide or GLOF.

Although climate change is not directly linked to the occurrence of earthquakes, the indirect consequences of landslides puts the lives of Nepalese people at risk.

Ms Rai was one of these people. In April 2015 she was trekking with two tourists from Poland in Nepal’s Langtang region when a massive 7.8 magnitude earthquake struck.

The trio had stopped for lunch in a small house not far from the Langtang Valley.

“I felt moving, and if I feel a moving earthquake I always run out of the home,” said Ms Rai.

“I ran outside, and in five seconds the house was collapsed. The house I was inside of.”

Ms Rai and her two clients were unharmed, and were rescued by helicopter after being stranded for four days.

They were the lucky ones; 120 people in the area perished in the disaster, crushed by the earthquake and the avalanche that followed.

Langtang village was completely wiped out.

Sita Rai has been working as a Himalayan mountains trekking guide for 15 years. Picture: Chloe Strahan.

Tourism at risk

Nepal’s trekking industry brings thousands of tourists to the country every year. The devastation of the 2015 earthquake initiated a decline in tourists travelling to Nepal, but nearly two years later the number of travellers is back to normal.

However, according to Dr Rice, climate change will have an impact on tourists visiting Nepal, as the snow covered mountains are a landmark for international visitors.

“Many people in Nepal go there to see the snow and the glaciers,” he said.

If the snow continues to melt on the Himalayas, this will give tourists less incentive to travel to Nepal to see the mountains. Nepal relies on its tourism and trekking industries, and if that declined then the economy would suffer.

Part of the Annapurna mountain range at sunrise. Picture: Chloe Strahan.

What can the world do?

In January 2017, the Nepal's President Bidya Devi Bhandari announced: “Nepal wishes to play a proactive role to protect biodiversity and repel the negative impact of climate change.”

The President said Nepal was facing the brunt of climate change in form of melting ice and threats of deforestation and glacial lake outburst floods, even though Nepal’s contributions to global warming are negligible compared to the rest of the world.

Dr Rice believes that providing Nepalese people with alternative solutions to things like deforestation will help improve their lifestyles and the negative impact of climate change.

“We empower them by providing sources of clean air, clean water, education and so forth, then the future’s bright and there’s lots of opportunities for everyone,” said Dr Rice.

“In Australia people tend to think that we don’t actually contribute much to climate change, that’s simply not true. We have one of the highest emissions per capita on the planet,” said Dr Rice.

According to Dr Rice, recent studies by CSIRO and other institutes in Australia show Australians are concerned with climate change, and understand the link between increasing extreme weather events and climate change.

He says a lack of political will is the only thing that is stopping solutions being put in place.

“Australians have a huge role to play. We are part of the problem, but we are also a huge part of the solution.