Urgent answers needed on tuberculosis, experts say

On World Tuberculosis Day, experts on the disease gathered at the Peter Doherty Institute in Melbourne with a message: we want to eliminate tuberculosis and we need the right tools to do it.

By NICHOLAS KAMENIAR-SANDERY,

health and science editor

An outbreak of multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) on Australia's doorstep this year has focused experts on the urgent need for better answers on treating the deadly disease.

The outbreak on Daru Island near the Australia-Papua New Guinea border worsened while health responders complained of poor funding from the PNG government.

The rise of MDR-TB has led to the diminishing effectiveness of current tuberculosis medicine, with experts saying more effective tools are needed to identify drug resistance early in treatment.

Victorian Tuberculosis Program medical director Associate Professor Justin Denholm, speaking at a seminar on World Tuberculosis Day last Thursday, said global tuberculosis treatment efforts needed to have their foot on the gas pedal. The seminar – Community-based Tuberculosis Programs to Reach, Treat, and Cure Everyone – was held at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity in Melbourne.

“What Papua New Guinea shows us is that if you stop accelerating, you get rapidly out of control,” A/Prof Denholm said.

“This is a period of a relatively short time where people have not been attending to that basic infrastructure and we’ve seen a massive explosion of the world’s worst TB incidents.”

The Victorian Tuberculosis Program is advocating an 18 per cent reduction in tuberculosis cases per year globally. This is similar to the End TB Strategy of the World Health Organisation, which aims to reduce TB deaths by 95 per cent and TB infections by 90 per cent by 2035.

What is tuberculosis?

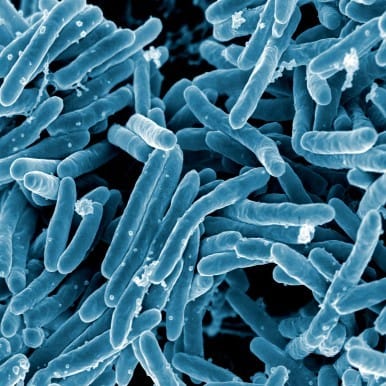

Tuberculosis is a bacterial infection, typically in the lungs, that infects a third of the world’s population. Tuberculosis typically exists in a dormant form, known as latent TB, which shows no harmful symptoms. A person can be unknowingly infected with latent TB for long periods, sometimes years, before it becomes active and they begin showing symptoms.

TB is known to activate in response to a weakened immune system or weakened lungs, with triggers including old age, smoking, recreational drug use, and HIV infection.

Research shows vitamin D deficiency may also correlate with TB activation, however it is not known if vitamin D supplements can help to combat TB after it activates.

Once active, it causes symptoms such as long periods of coughing, coughing up blood, chest pains, fever, and unexplained weight loss. TB has a high mortality rate if not properly treated. In 2014, about 1.5 million people worldwide died from TB, according to a report by the World Health Organisation. It is the leading killer of people suffering from HIV.

Tuberculosis in Australia

Australia has one of the lowest rates of TB in the world, at about 5.5-5.8 per 100,000 population. Despite this, there has been a slight but steady increase in TB notifications since the 1980s, alongside Australia's increase in migration. About 90 per cent of TB cases in Australia occur in migrant communities.

Migrants may come to Australia with a dormant TB infection that activates and manifests symptoms later in their life. Migrants are screened for active TB, but they are not currently checked for dormant TB.

TB is also much more common in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities than in the white Australian population. This is likely to be a result of inadequate medical facilities to provide treatment in closely knit Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

The Victorian Tuberculosis Program runs contact tracing to try and minimise TB infection spread in Melbourne and Victoria. Contact tracing is done in response to a TB notification, and involves identifying and performing diagnostic tests (such as the tuberculin skin test) on people who have regular contact with the patient. These contacts are usually family, friends, communities, and peers at the patient’s school or workplace. Diagnostic tests are usually run multiple times over several months.

The VTP notifies the Department of Health of any confirmed cases of TB infection.

Multi-drug-resistant TB and whole-genome sequencing

Multi-drug resistance means the bacteria have evolved defence mechanisms to fight the drugs used to treat the disease. In the case of TB, this means that certain drugs, such as streptomycin, will not work as a treatment against certain strains of TB. This is an extra challenge for doctors and patients if they cannot identify the specific resistances an infectious strain of TB may have early in the treatment.

Whole-genome sequencing will be a useful way of identifying specific drug resistances in TB strains and providing more adequate treatment to patients, according to the Doherty Institute's Associate Professor Timothy Stinear, who is also scientific director of the Doherty Applied Microbial Genomics Centre.

In a study published in Microbial Genomics, researchers performed whole-genome sequences of TB isolates collected from a single patient over a 21-year infection timespan to demonstrate how drug-resistance in TB evolves. The patient, an East Timorese woman who migrated to Australia in October 1990, had 14 years of treatment for MDR-TB, with treatment altered multiple times when the TB strain evolved resistances to several of the medications.

The paper shows that the form of drug-resistance identification available in 1991 was inadequate for determining effective treatment. This caused the infection to be treated improperly, allowing the bacteria to fester, evolve, and strengthen.

“If a genomic approach had been available in 1991,” the study says, “knowledge of this resistance profile at the commencement of treatment may have prevented exposure to unnecessary toxic drugs, and allowed composition of an effective regimen that included enough active drugs to prevent emergence of further resistance.”

A/Prof Stinear said he wanted whole-genome sequencing to be widely used in MDR-TB treatment around the world.

“We have this technology now. We can use it now. This is the direction we should be going,” he said during his presentation at the Doherty institute. The technology is yet to be widely used in medical diagnosis.

References

Outbreak of MDR-TB on Daru Island (2016 update)

Eric Tlozek “Tuberculosis outbreak in Papua New Guinea worsens, as health workers plead for promised funding” 11.01.2016 (link)

Vitamin D deficiency correlation with TB activation

Katherine B. Gibney, Lachlan MacGregor, Karin Leder, Joseph Torresi, Caroline Marshall, Peter R. Ebeling, and Beverley-Ann Biggs Vitamin D Deficiency Is Associated with Tuberculosis and Latent Tuberculosis Infection in Immigrants from Sub-Saharan Africa Clinical Infectious Diseases 2008 46: 443-446. (link)

World Health Organisation Report on Tuberculosis 2015

World Health Organisation (2015) Global tuberculosis report 2015 (link)

Department of Health report on Tuberculosis Notifications in Australia in 2012-13

Australian Government Department of Health (2015) Tuberculosis notifications in Australia, 2012 and 2013 (link)

Whole genome sequencing of MDR-TB isolates over 21-year infection period

Meumann E, Globan M, Fyfe J, Leslie D, Porter J, Seemann T, Denholm J, Stinear T. Genome sequence comparisons of serial multi-drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates over 21 years of infection in a single patient 26/11/2015. M Gen 1(5): doi:10.1099/mgen.0.000037 (link)